Conducting a large-scale educational research study is a complex and demanding task. While much of the spotlight often falls on findings and policy recommendations, what remains less visible, but equally crucial, is behind-the-scenes work, particularly data management. In contexts like Pakistan, where the educational research infrastructure is still developing and there is a visible push towards evidence-driven decisions, data management processes need to be standardised to ensure the quality and credibility of results. In every research project, data management should begin even before data collection starts and continue through to the final stage of analysis.

This blog draws on our experience of managing data for large-scale studies, funded by DARE-RC, focusing on student learning outcomes and classroom practices along with other aspects in various types of schools across the diverse regions of Pakistan. In each study, there were 3500+ students and 400+ teachers. The data were gathered through achievement tests, classroom observations, survey questionnaire and interviews. Operating at this scale meant confronting multiple challenges including logistical, linguistic, and technological. We discuss how the core team developed and implemented standardised data management protocols and navigated challenges of scale, standardisation, and alignment. In other words, we present an insider’s look at how we organised, coded, marked, entered, and cleaned quantitative data and transcribed and coded qualitative data to make sense of large-scale data.

Our aim is not only to document procedure, but to provoke critical reflection on the labour and care required to produce trustworthy educational evidence in the Global South. We hope this will be useful for future researchers to manage research projects.

Ax Expert’s Advice on Rigorous Data Management

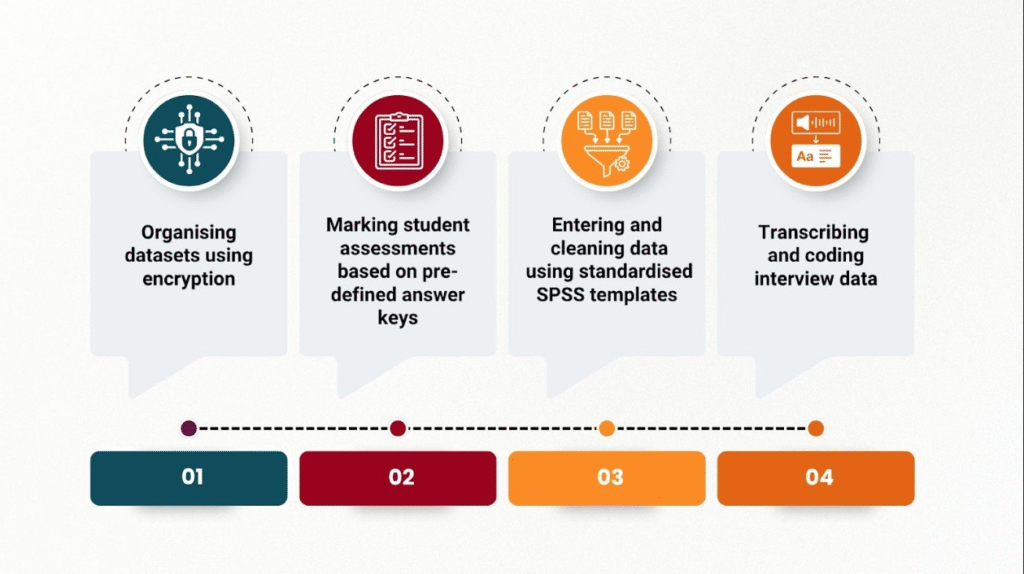

The process involved four key steps for data management considering the nature of nationwide studies. These include: 1) organising datasets using encryption, 2) marking student assessments based on pre-defined answer keys, 3) entering and cleaning data using standardised SPSS templates, and 4) transcribing and coding interview data. Dedicated central teams for each study were oriented on protocols and followed a comprehensive set of procedures at each stage of data management.

Step 1: Data Organisation with Encryption

Our data management journey began immediately after completing fieldwork in the first region. Each student’s learning assessments (Science and Mathematics Achievement Tests), demographic sheet, and survey questionnaires were bundled together and assigned a unique encryption code. The same approach was followed for each teacher’s data, including teacher questionnaires and classroom observation rubrics. This “encryption” was not digital encryption in a cybersecurity sense, but rather a structured system of alphanumeric codes assigned manually to ensure anonymity and traceability.

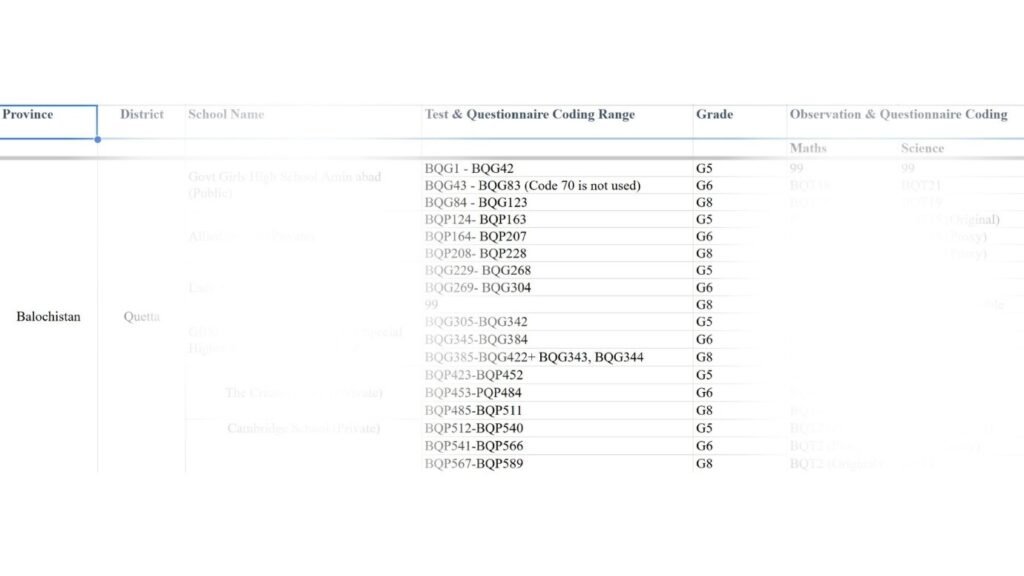

An example of a student data code is BQG1, where B represents Balochistan, Q stands for Quetta, G denotes government school, and 1 is a unique sequential number. Similarly, an example of a teacher data code is BQGT1, where B represents Balochistan, Q stands for Quetta, G denotes government school, T indicates teacher, and 1 is the unique sequential number.

These individual-level documents were then organised into labelled ‘school packs’ to enable easy access and quick referencing. To ensure that teacher data could be linked with student outcomes, we developed an Excel-based tracking sheet, aligning each teacher’s code with the codes assigned to their students, as presented in the image below. This system allowed us to synchronise datasets efficiently and prepare them for merging at later stages.

Image displaying data organisation on an Excel sheet

Step 2: Marking Student Assessments with Reliability

Assessing students’ performance in achievement tests, particularly constructed response questions, requires careful attention to consistency and fairness. To standardise the marking process, we developed detailed answer keys and trained all research assistants involved in assessment scoring. Additionally, we ensured that assessors had subject-matter knowledge as well as language proficiency.

Initial assessment was carried out collaboratively for a subset of schools, allowing the team to calibrate their approach and resolve any discrepancies. Monitoring by the core team was a consistent feature of the marking process in order to maintain quality. We also assessed inter-marker reliability, which refers to the consistency with which different evaluators score the same test responses. To ensure fairness and accuracy, we established a threshold of at least 80% agreement between markers before proceeding to mark test papers independently. This reliability did not emerge spontaneously; it was sustained through regular audits and mandatory random rechecking of papers before data entry.

Step 3: Structured Data Entry and Cleaning

Separate databases for student and teacher data were created using SPSS (v27). A shared SPSS template with a fixed variable structure was developed to maintain consistency. This structure specified uniform variable names, labels, and coding schemes (e.g., for student demographics, questionnaire, test, teacher characteristics, and classroom practices), ensuring that data from different sources could be entered and analysed in a standardised way. Centrally hired research assistants, trained by the core team, were assigned grade-specific responsibilities for student data entry. Teacher data, being more manageable, was entered by a single person to ensure uniformity and reduce variability.

We enforced a strict protocol prohibiting any changes to the variable structure in the SPSS template without prior approval from the core team. This protocol ensured consistency in the datasets, which in turn made it easier to merge data entered across different grade levels. Data entry was complemented with routine random spot checks to immediately identify and correct any errors.

Before data analysis, comprehensive data cleaning for the entire data was carried out soon after the completion of the data entry process of both sets of data by running frequencies of each variable and rectifying emerging errors. Since, we had multiple data files, and it is essential to merge them together. Both the data sets (i.e., students’ assessment data and classroom observation data) were merged in a single file in order to make them ready for statistical analysis. After merging the data sets, the complete data set was double-checked in order to ensure that the observation data of teachers are placed appropriately with respective students’ test scores.

Step 4: Managing and Analysing Qualitative Data

The qualitative component of one of the studies explored how teachers conceptualise and implement participatory teaching strategies. With informed consent, all twenty-one interviews, ranging from 45 to 60 minutes, were audio-recorded and transcribed in their original languages to preserve contextual accuracy. Selected quotations were later translated into English for use in reporting. The analysis involved a multi-phase process, including, 1) open coding to identify meaningful segments; 2) categorisation of similar codes; and 3) theme development to synthesise emerging patterns.Two research assistants were trained and tasked with independently coding each transcript. Their individual codebooks and coded transcripts were reviewed by a third senior research assistant to ensure accuracy and consistency. This triangulated approach yielded an inter-coder reliability score of 80%, considered acceptable in qualitative research. The lead researcher from core team subsequently grouped open codes into categories and developed themes, which were used in the final analysis and reporting.

Good Data for Enhanced Credibility

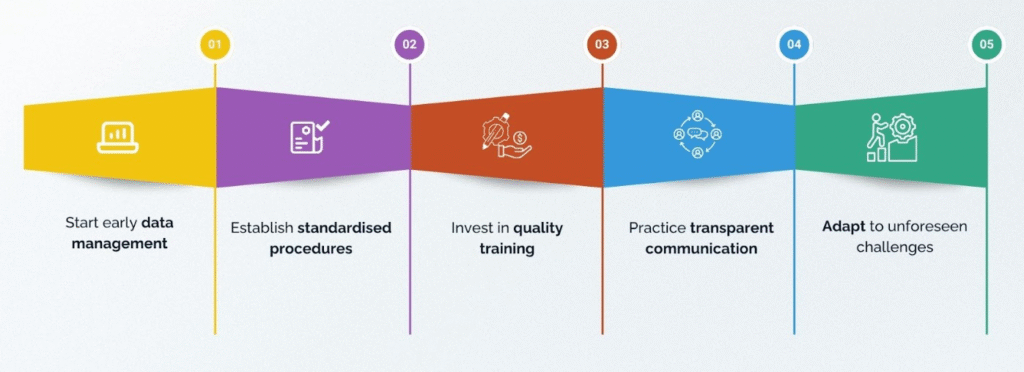

Our experience offers several key lessons for researchers managing large-scale datasets.

First, data management should begin early, ideally during the planning phase, rather than after data collection has concluded. Second, establishing standardised procedures, such as using uniform templates and shared coding systems, reduces errors and improves consistency across teams. Third, investing in training is critical, as research assistants require structured guidance and oversight to maintain data quality. Fourth, transparent communication within the team fosters collaboration and supports data integrity throughout the process. Finally, while adherence to protocols is essential, teams must remain flexible and responsive to unforeseen challenges during data management.

In a nutshell, data management may not be the most visible part of research, but it is undoubtedly one of the most essential. In large-scale studies, where the risk of error is amplified, a careful, transparent, and collaborative approach to handling data can significantly enhance the quality and credibility of research findings. By prioritising robust data management practices, we not only strengthen the integrity of our evidence but also uphold the standards of responsible and ethical research.

Authors: Aisha Naz Ansari (Research Specialist, Aga Khan University, Institute for Educational Development (AKU-IED), Sohail Ahmad (PhD Candidate, University of Cambridge), Dr Sadia Muzaffar Bhutta (Associate Professor at AKU-IED), and Dr Sajid Ali (Professor at AKU-IED)

Editor and Quality Assurance: Dr Sahar Shah (Senior Research Manager, DARE-RC)

Copy-Editor: Maryam Beg Mirza (Assistant Consultant, Education at OPM)

Design: Sparkom Media

The views expressed in this blog are that of the authors and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners

This blog is based on the findings from the Individual Resource Paper (IRP) submitted by the author in completion of the NIMS Course – Cohort October 2024. The topics were provided by DARE-RC and the IRPs were reviewed by Dr Sahar Shah (Senior Research Manager, DARE-RC), as part of the DARE-RC capacity strengthening initiative.

Despite numerous initiatives, Pakistan’s education system continues to face serious challenges caused by political and economic instability, outdated curricula, gendered exclusion, and inadequate infrastructure. Overcoming these challenges is essential because education is the key driver of national development and the cornerstone of socio-economic progress.

I draw critical insights from my recent research paper, “Modernising Pakistan’s Education: Blueprint for Reforms”, submitted as my Independent Research Paper (IRP) towards the end of my course at the National Institute of Management Sciences (NIMS) in December 2024, to highlight crucial and actionable paths for progress.

Outdated Syllabi and the Theory-Practice Gap

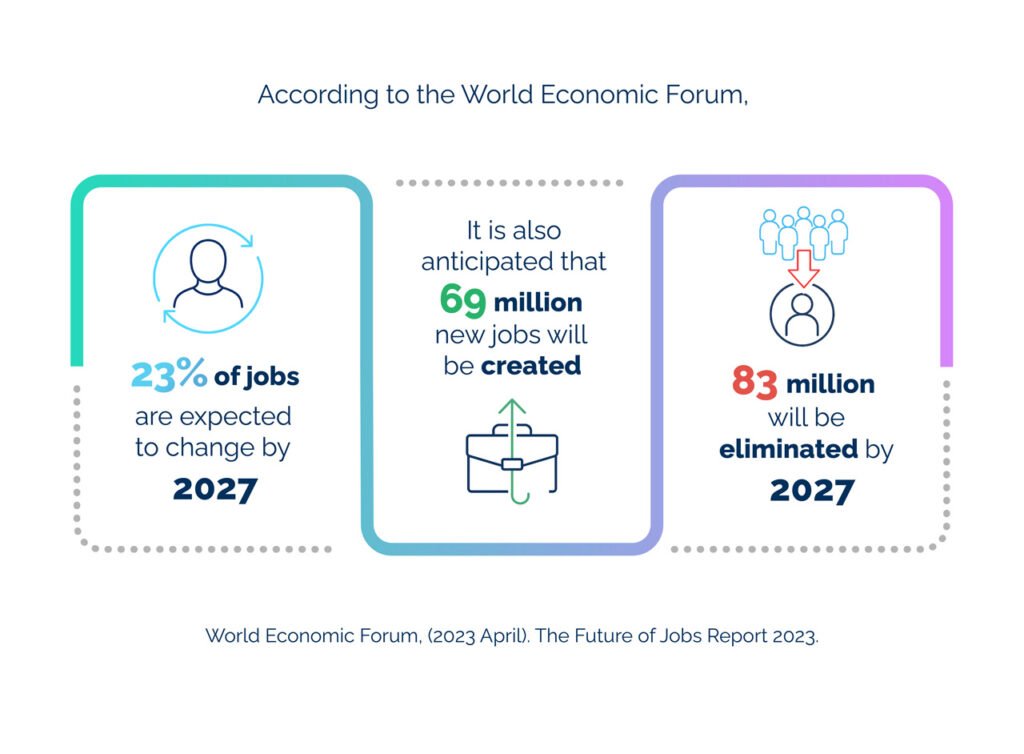

According to the World Economic Forum, 23% of jobs are expected to change by 2027. It is also anticipated that 69 million new jobs will be created and 83 million will be eliminated by 2027. These shifts demand rethinking about how we should prepare our students, not just theoretically, but also practically. In Pakistan, there is a significant divide between academic training and practical workforce requirements. Many universities in Pakistan still follow old curricula with very little focus on hands-on learning coupled with a significant gap in structural equity. There is also inadequate practical exposure to critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Very few universities give internship opportunities to students although the need for experiential learning enhances students’ likelihood of getting employed in the future after completing their education.

Although the country has shown some progress towards aligning with international standards, fundamental gaps persist prominently. For instance, students of Computer Studies or Computer Science do not apply their programming skills in practical scenarios, there is no proper training, and even basic software is unavailable or pirated. This gap between academic theory and its real-world application continues to deter actual modernisation.

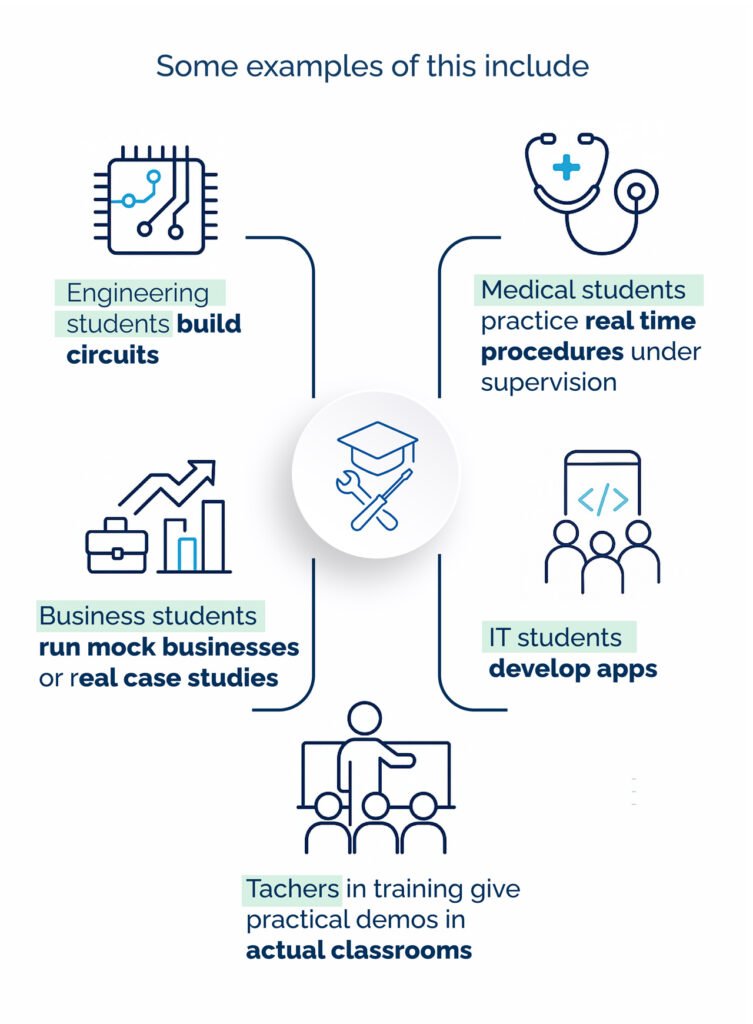

Hands-on-learning refers to learning by doing and to enabling students to actively engage in practical activities instead of simply reading and listening to theory or to engaging in route-learning. Students are encouraged to perform experiments and simulate scenarios or work on projects and apply their learnings to practice.

Inculcating this approach is important to improve comprehension, understanding and retention and to develop creative thinking skills and ultimately prepare the students for real world challenges.

Gender Discrepancies and the Urgent Need for Inclusivity

Educating women not only empowers them individually but is vital for the prosperity of households and communities. An informed woman is a strong woman, and an educated woman is a catalyst for social change. Empowering women through education would elevate families, communities, and the whole nation.

In Pakistan, the gender gap in access to higher levels of education is quite alarming, hampering both national progress and social development. In many regions, female education is given less priority, especially in rural areas, security-vulnerable regions, and conservative communities. This trend is especially visible in remote areas in Balochistan, interior Sindh, and certain tribal districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, specifically the Newly Merged Districts (ex-FATA). In such areas, early marriages are common, and parents give higher priority to the education of boys over that of girls for various economic, social, and cultural reasons. Therefore, girls have limited access to schools, leading to depreciated opportunities to advance to higher education.

Some methods to improve girls’ and women’s access is to launch targeted scholarships and stipends for female students, run awareness campaigns, and engage with media, religious leaders and communities to shift perspectives on the value of education for girls and women. Campuses should be made safer and secure in line with the needs of female students, especially in remote regions, to curb concerns for security by family and community members.

Access is only the first step, not the only one. Quality of learning and guidance for female students is equally crucial to ensure Pakistani girls and women are equipped with the most relevant knowledge and skills to compete in the employment market. Pakistan has a dearth of all-encompassing learning environments and mentorship for female students. This is coupled with limited representation of women in academic leadership. Female students could also significantly benefit from career counselling programmes focused on young women which possess an informed understanding of their obstacles and ambitions.

A Need for Action, Reform Through Innovation

Incorporating capstone projects, student internship opportunities, and real-time data analysis into curricula is a serious need of the time because the 21st century job market is rapidly evolving. Modernising education in Pakistan must go beyond policy drafts and new slogans; it must reform deeply entrenched systems bylistening to students and educators, especially girls and women, andenable them to acquire new and relevant skills and attitudes.

The path to modernising education in Pakistan is grounded in inclusivity, fostering innovation, and ensuring effective policy implementation. It is also important that introducing reforms in the curricula, improving the infrastructure, empowering women and promoting hands-on learning must not be the only policy goals, rather they are dire requirements to allow us to work upwards. If we want to equip young Pakistanis to be prepared for the challenges of the 21st century and improve social and economic conditions, it is necessary for the education system to move beyond traditional norms and unmet commitments. It is time to act, as dormancy will cost us far more than the challenges of reform.

Author: Ghazala Anbreen is a senior civil servant from the Information Group based in Islamabad, Pakistan, with wide experience in education, public diplomacy, and policy reform.

Editor and Quality Assurance: Dr Sahar Shah (Senior Research Manager, DARE-RC)

Copy-Editor: Maryam Beg Mirza (Assistant Consultant, Education at OPM)

Design: Sparkom Media

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.

Adolescents in Pakistan Live in an Increasingly Volatile Climate

Pakistan ranks fifth globally on the Climate Risk Index, and is expected to see increasing occurrence and severity of extreme weather events. The country is affected by multiple climate risks; a warming rate considerably higher than the global average, water scarcity and intensifying droughts alongside flooding since 2010, and worsening air quality.

An adolescent in Pakistan today – i.e. a young person between the ages 10 and 19 years – will experience more floods, crop failures, droughts, heat waves and air pollution over their life time than an adolescent in the 1970s. Extreme climate events bring with them staggering human and economic costs[i], exacerbating existing vulnerabilities and widening inequalities.

Young people are going to be the primary bearers of the high human and economic costs of climate change, which threaten their health, education, well-being and futures. Younger men and women and the differently abled from marginalised backgrounds are disproportionally disadvantaged due to their precarious and limited access to basic services, social protection schemes and other coping mechanisms. Their heightened exposure to multiple extreme climate events raises vulnerabilities manifold and leads to the transmission of negative shocks across generations, such as reduced incomes and opportunities for young people.

Extreme Climate Events Disrupt Education Trajectories

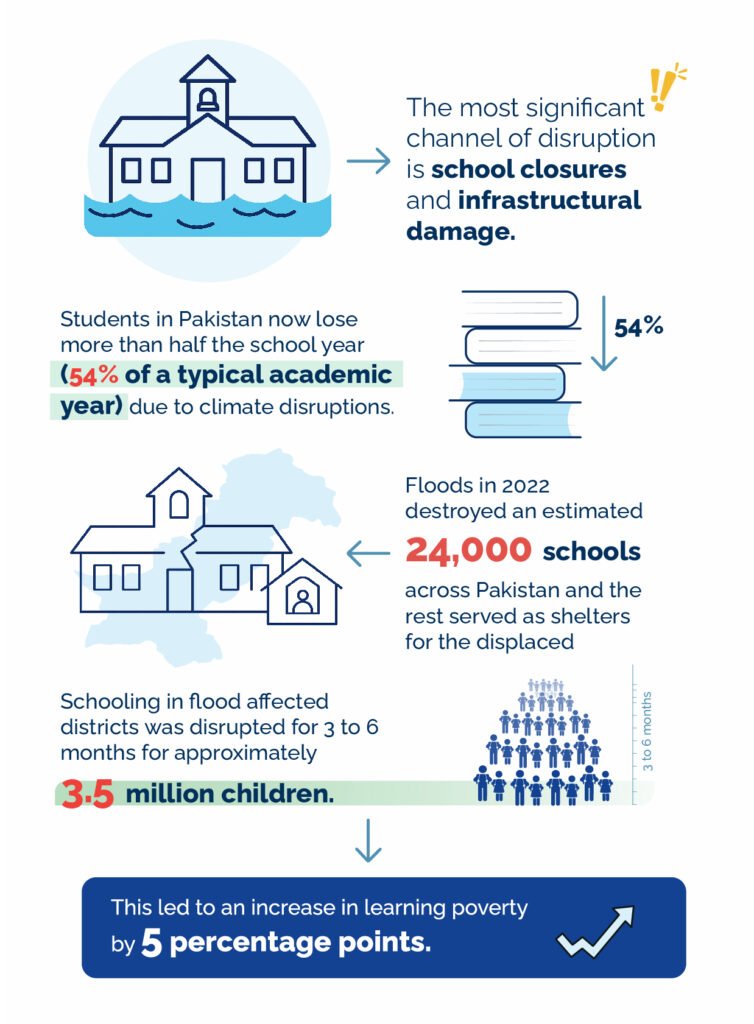

Extreme climate events damage service delivery infrastructure and compromise the ability of students to access, engage and learn in schools. Almost all children around the world are now exposed to at least one major climate shock in their lifetime. This exposure is far worse for adolescents and children in the global South, where recent improvements in access and learning have been reversed due to worsening severity and frequency of extreme climate events.

Figure 1. Consequences of Climate Disruptions for Educational Outcomes

Air pollution and heat waves are now routinely associated with school closures and prolonged school holidays. Schools in Lahore remain closed for between 2 to 4 weeks on average every year during smog season. Evidence from countries in the global South shows that high heat reduces in-class engagement, concentration/ability to focus and is associated with lower learning outcomes.

This disrupted access is temporary for some but permanent for others. Girls in particular are especially vulnerable. A large number of girls in Sindh dropped out of school because of flood-related closures and never went back. Countries across South Asia, including Pakistan have registered a rise in early marriages for girls as a direct response to economic shocks or insecurities and displacement linked to climate. The health and economic shockwaves triggered by extreme climate events push millions of people into poverty, resulting in both girls and boys dropping out of schools

Seeking Solutions within Lived Experiences

There is little documentation of the ways in which climate shocks compound threats posed by poverty and underdevelopment to the education and life trajectories of millions of young people in Pakistan. Exposure to and experience of climate change is likely to vary by geography, gender and socio-economic class. While proposed adaptation strategies suggest a role for students as change-agents, this role remains undefined in the context of countries and communities in the global South. Imagined and designed solutions for mitigation and adaptation must account for the voices and experiences of these young people.

Some evidence of climate distress is beginning to emerge from studies in the global South. However, for Pakistan there is at best anecdotal evidence on the experiences of communities living through the rapid climate changes. The public, academic and policy discourses feature policy makers, teachers, journalists and climate activists; yet none speak directly to the young people.

As we move to develop strategies to increase climate resilience, it is imperative that we look to the communities and the students themselves. The climate and education policy actors, and service design and delivery structures must imagine active and substantive roles for adolescents in climate risk mitigation and adaptation strategies, rather than considering them passive victims of climate shocks. This requires ensuring adolescents are supported through required knowledge and skill-building for living in and coping with a volatile climate. For example, Pakistan can embed disaster education into the existing curriculum in much the same way as that done in other countries as Cambodia and Thailand have done. Such changes to the curriculum and other steps need to be informed by young people’s lived experiences of the types of threats they face, be it drought-related water stress, food insecurities or extreme heat.

Figure 2. DARE-RC Study on Schooling Strategies and Climate Change

[1] The cost of illness and premature death from air pollution was estimated at equivalent to 2% of GDP annually in 2016. A third of the country underwater with 33 million people displaced. The total damage due to these floods was estimated to be equivalent to 4.8% of the years’ GDP, while recovery and reconstruction needs were projected to be 1.6 times the budgeted national development expenditure for 2023. The floods also caused a decline of in GDP estimated at nearly 2.2% of FY22 GDP.

Authors: Dr Hadia Majid (Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Economics, LUMS), Dr Rabea Malik (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives), and Ms Fatimeh Munawar (Research Assistant, DARE-RC)

Copy-Editor: Maryam Beg Mirza (Assistant Consultant, Education at OPM)

Quality Assurance: Dr Sahar Shah (Senior Research Manager, DARE-RC)

Design: Sparkom Media

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.

We joined the Education World Forum to explore how global education systems are navigating AI, funding gaps, and the future of skills.

The Education World Forum is one of the most influential global gatherings in education policy, bringing together ministers, funders, and thought leaders to debate the most pressing challenges facing education systems today. Now in its 21st year, EWF 2025 featured an impressive gathering of over 1000 delegates including Education and Skills Ministers from 135 countries across the world, ranging from the most developed economies to low-and lower middle-income countries. From artificial intelligence and digital transformation to education financing and the future of vocational skills, the forum offers a rare opportunity to hear first-hand how governments and partners are shaping the future of learning worldwide.

This year’s forum surfaced a strong consensus: education systems are under pressure to adapt—and fast. With a growing funding gap, accelerating technological change, and an urgent need to equip learners for an uncertain labour market, the global education agenda is shifting. But how are different countries responding, and what lessons might apply more broadly to international development?

Digital transformation in education

One of the most talked-about topics was how education systems are navigating digital transformation. Governments are asking difficult but necessary questions: How do we harness the benefits of new technologies while keeping learners at the centre? How do we ensure equal access? And what role should artificial intelligence play in the classroom?

National strategies varied. China shared a vision for intelligent education, the UK voiced a commitment to develop generative AI guidelines, and Finland highlighted efforts to limit digital device use in schools to better support students’ social development. Several countries also raised concerns about the digital divide and called for urgent investment in devices and connectivity.

What stood out was the shared recognition that while digital tools are essential, they are not a substitute for teachers. Relationships, empathy, and human connection remain core to learning, and technology must support, not replace those elements.

Investing in teachers, enhancing the appeal of the teaching profession, reducing excessive workload and improving working conditions, and offering ongoing peer-based professional learning opportunities to teachers are some of the most impactful solutions adopted by the world’s highest performing education systems. Equally, understanding how children learn best, cultivating a ‘growth mindset’ in all students, and focusing on learning both inside and outside the classroom, has demonstrated transformative results across individual students, schools and education systems.

Our Principal Consultant, Saima Anwer, (third from right) with Wajiha Qamar, Minister of State at the Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training (fourth from right), Maria Wyard, Group Head Health, Education and Demography British High Commission Islamabad (fifth from right), and other members of the Pakistan delegation

Rethinking education financing

Another central theme was how to address the global education funding gap, now estimated at $97 billion. There was widespread agreement that education is not a short-term cost but a long-term investment. Ministers and donors alike emphasised the need to unlock more resources and make better use of existing ones.

Innovative solutions featured prominently, including impact investing, blended finance, and debt swaps. Encouragingly, the private sector and philanthropic foundations are showing greater interest in education as a viable investment area, not just a social obligation.

At the same time, with more than 70% of funding still coming from governments, public finance remains critical. Many speakers called for greater efficiency, stronger evidence, and smarter spending to ensure funds reach those who need them most.

The future of skills and vocational education

Another prominent theme discussed throughout the conference was skills and vocational education, highlighting its potential to drive inclusive economic growth. Speakers stressed that vocational training should not be viewed as a fallback option, but as a first-choice route to high-quality employment.

Changing perceptions will require deliberate action. Countries shared examples of partnering with industry to shape curricula, investing in modern training centres, and building prestige around vocational pathways. Practical measures included income-contingent loans, employer-backed national training funds, and lifelong learning policies that extend beyond the classroom.

As one panellist put it: “We used to learn to do our work. Now, learning is the work.” This shift requires systems that support continual upskilling and reskilling in response to a changing world.

Why this matters

The discussions at the Education World Forum reflected a growing convergence around key priorities for education systems: responsible integration of digital technologies, sustainable financing models, and the need to align skills development with evolving labour market demands.

For those working on policy reform and systems strengthening, these insights offer a comparative view of how different countries are approaching common challenges. They also underscore the importance of cross-sector collaboration and the role of evidence in designing adaptive, inclusive education policies.

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.

With the world’s largest population of out-of-school children, Pakistan is facing an education emergency that will have far-reaching consequences in economic, social, and health development for at least the next two generations. Addressing this issue is challenging because education is chronically underfunded in Pakistan, with only 1.9% of GDP spent on education in 2023. In comparison, India, Afghanistan, and China all spend 4% or more of their GDP on education.

Pakistan faces numerous development challenges that are expected to intensify as the economy continues to struggle, climate change worsens and concerns about a global recession escalate. How, then, do policymakers prioritise limited financial and human resources to maximise school enrolment?

Our team is working on the Equity Equation Project: Predictive Modelling of Policy Impact on School Enrolment, under DARE-RC. This study aims to develop agent-based simulation models (ABM) that predict school enrolment decisions made by families facing marginalisation in response to policies in education and other sectors. As part of initial investigations, the team has completed a literature review on push and pull factors that create barriers to school enrolment. The team has also analysed publicly available data from Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) 2019-2020 and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) 2017-2018 to identify individual and household level factors that are highly predictive of school enrolment.

Push and Pull Factors for School Access

Our team conducted a literature review that revealed a number of factors within a child’s life which influence school enrolment. These include children’s immediate family, community, social, and national environments. We examined the literature across various contexts, particularly in the Global South, to identify barriers to education. These include push factors, or school-related challenges to enrolment, such as a shortage of schools, and schools that do not support disability, have poor teaching, and insufficient facilities. Conversely, pull factors are external and contextual barriers to education, such as financial and family needs, climate crises, or sociocultural expectations. We were able to organise these factors into an ecological systems theory model (EST), teasing them out to understand the intersections of barriers across several layers of influence, ranging from the individual level (microsystem) to the time-bound and historical level (chronosystem).

Push and Pull Factors that Create Barriers to School Access Using EST

Credit: Shahbakht Mubarik, Senior Education Research Associate, Equity Education Project

The literature revealed that two cross-cutting barriers impact school enrolment: gender discrimination and poverty. These affect school enrolment at every ecological system level from the individual family to large-scale national policies. Gender discrimination can be seen in policies that do not protect or value women in the workforce, in community narratives around women’s education, and in household decision to restrict girls’ participation in education. Economic poverty also has a similar impact. It leads to limited funds for school expenses, creates low levels of investment on basic education, inhibits access to important technological learning tools in remote communities, and forces families to put their children in the labour market to ensure everyone has enough to eat.

These barriers to school enrolment are well-explored in the global literature and are clear. We further wanted to explore how these various factors predict access to education within Pakistan’s context, and which predictive factors rank the highest.

What Really Determines Enrolment?

We conducted predictive analyses with neural networks and random forests using the MICS data for the Lahore division and the PSLM data for the Nankana, Lahore, Kasur, and Sheikhupura districts. Random forest models generated the most accurate predictions on school enrolment, with around 90% accuracy on the MICS and 83-85% accuracy on PSLM, depending on the district. We ranked the importance of each factor in predicting school enrolment, and the interaction of features in predicting access to education by using SHAP decomposition in tandem with the trained models.

Interestingly, our initial predictive analysis revealed that the proxies for socioeconomic status (SES) predict access to education, specifically mobile phone ownership, household wealth, and parental education. In the MICS survey, we ranked some of the most important features that included whether the child enjoys reading, parental education, household wealth, and disability status, among others.

MICS Lahore Division SHAP Feature Importance Plot for School Enrolment for 5-16 Year Olds

PSLM was more granular and enabled us to look for changes across districts within the Lahore division. We saw similar trends suggesting that access to food, housing, heating, water, and WASH facilities in the home predicted school enrolment (though proxies for these changed over the districts). This indicates that SES remained a crucial predictive factor even as the context changed.

Only in Nankana was gender an important predictor of educational access.

PSLM Kasur District SHAP Feature Importance Plot for School Enrolment for 5-16 Year Olds

While we certainly expected to see many proxies for SES as highly ranked features, we anticipated that some of the other diverse barriers and enablers from the literature review would also be included, particularly gender. In the face of so many SES proxies, other features simply did not rank in the top 20 features as often or at all.

The Big Questions

Our research team is deeply committed to several core values and ideas, one being that evidence-informed decision-making is one of our strongest enabling tools for making positive changes. Considering how important the poverty indicator is in both the literature and the secondary predictive analyses; we considered possible implications:

What if the most critical key to enrolment is centred on alleviating poverty, while providing access to education through better schools, better roads, addressing cultural barriers, etc. is secondary?

In answering these questions, we keep in mind that data-use experts emphasise that understanding data limitations is key to making evidence-informed decisions. We revisited the literature and the available secondary data, probing for assumptions and missing information, which helped us identify data gaps that we hope to close in our study. Given the high accuracy of our current models on test data, incorporating additional factors may yield diminishing improvements in predictive performance. We have outlined some of these gaps and their suggested areas of investigation.

Missing Data: First, not all factors found in the literature are captured in the secondary survey data. For example, the literature says that safe, reliable, and affordable transportation is an important enabling factor for school enrolment, but the PSLM and MICS data does not provide information on the relative availability of nearby schools or transportation to a school. Attitudes and experiences related to concerns for gender-based safety are not included in these surveys, nor are the perceptions of local schools.

We hope to uncover the community-level importance of factors found in the literature which lack consolidated data. We also believe this will help us suggest important data points for future collection and analysis to our partners, particularly the Pakistan Institute of Education (PIE).

Intersections and Directionality of the Data: Predictive analysis using neural networks allows us to rank the importance of factors non-parametrically, capturing complex feature interactions and how they influence the outcome. However, there is a limit to this analysis. While the interactions of multiple factors (student’s gender, type of housing, food security, etc.) and their resulting outcomes are captured in the models, we cannot visualise how they interact with each other. For example, how do multiple indicators of socioeconomic status interact with gender to influence outcomes? Our predictive analysis can only tell us that they interact, not how. As a result, our ability to explain complex multi-dimensional interactions is limited.

The study uses primary qualitative data at the family level to unpack and deentangle how these factors interact to influence decision-making for school enrolment.

Granularity of the Data: While the MICS data is representative at the division level, the PSLM data allowed for a more granular look at the districts within the Lahore division. It also revealed some differences between how important features change from district to district. How would features change if we could move to an even smaller administrative unit such as the tehsil or union council? If we were to look at communities that have high levels of religious and linguistic minorities, how would the results be different? The literature reveals that these demographic differences create an intersectionality of experiences, pressures, and push and pull factors that may influence school enrolment decisions. Therefore, the ability to examine such communities would give insight into how these intersections impact decision-making.

Our team will carefully select sites having historically marginalised communities and conduct qualitative data collection to ensure these intersections are captured. We will also work with government partners to explore the possibility of using more granular data sets for future predictive analysis.

Contextual Nature of the Data: As this short project focuses on creating an ABM for proof of concept, we chose to work on targeted, manageable, and accessible locations that are relatively stable in the Punjab province. As a result, we only looked at the secondary data from the Lahore division, which is not representative of the nation, or even Punjab as a whole. In other areas of Pakistan, issues of safety, gender, and school access may rank more highly as predictive factors, particularly in remote or unstable areas.

Our team anticipates planning to scale the project to other divisions and provinces in collaboration with key partners.

Next Steps

The Equity Education Project is a multi-stage, iterative project, combining quantitative and qualitative data to create simulations of possible policy outcomes. Our next step is a qualitative investigation of how families perceive and interact with the factors identified in the literature and the secondary analysis to make school enrolment decisions. The findings will help us in enhancing our understanding of the existing data and allow us to identify and close data gaps.

Acknowledgements: We thank Hamna Dogar, Jawad Ali, Anees Amjad, and Shahbakht Mubarik for contributing to this work. Pak Alliance for Maths and Science (PAMS) is the implementation lead for the Equity Equation Project: Predictive Modelling of Policy Impact on School Enrolment.

–

Authors: Dr Jessica Albrent (Associate Professor, LUMS), Dr Farah Nadeem (Associate Professor, LUMS) and Dr Faisal Bari (Dean, LUMS School of Education)

Copy-Editor: Maryam Beg Mirza (Assistant Consultant, Education at OPM)

Quality Assurance: Dr Sahar Shah (Senior Research Manager, DARE-RC)

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.

By Ayesha Fazlur Rahman

Who amongst us has not looked at a group photo, searching for our own face first? In Pakistan, even the most seemingly inclusive textbooks will feature tokenised representations of marginalised groups. This impacts school-going children at a psychosocial level, who are searching to see their own or familiar faces, and disappointed that they are not there.

Looking beyond the semantics of politically correct terms like tolerance, inclusivity, diversity, equity or pluralism, the question arises: what do these terms stand for in the context of student learning content in Pakistan? Is an inclusive textbook different than an otherwise effective textbook? We take a snapshot of how Pakistani society can gain from textbooks that feature diverse representations, such as the contribution of non-Muslims’ in the creation of Pakistan, an athlete with a disability who is a Special Olympics gold medallist, or a family where gender roles are assigned to reflect contemporary trends.

Slow Progress for Fairer Representation

In Pakistan’s education sector, the policy regarding textbook content is implemented by the provincial textbook boards by setting the guidelines for textbook authors and reviewing the submitted manuscripts. Before making it to the review committee, a manuscript must comply with a list of 6-7 mandatory requirements which shape how inclusive the content will be. Some of these include:

“Inclusive principle: The school textbooks and learning material promote gender equality, human rights, and respect for all.” – Sindh Policy Textbook and Learning Material

“The manuscript is free from all kinds of social, regional, cultural, religious, gender, ethnic and sectarian biases.” – Punjab Textbook Evaluation Proforma for Reviewers

The word ‘bias’ may be interpreted in two ways. A bias-free manuscript may be one that is free of offensive (or hate) content that tarnishes a marginalised religion, ethnicity, geographical area or group of individuals. Additionally, taken in a broader sense, ‘bias’ also implies omissions, or neglecting to realistically and positively mention marginalised groups, their culture, achievements and lifestyle choices.

In language textbooks, marginalised groups are unseen in stories, not shown as integrated in nor contributing to communities. History and Pakistan Studies textbooks have largely been purged with hate content, especially for minority religions. Civil society organisations such as Lahore-based Centre for Social Justice have contributed to this progress by identifying and reporting on such content while sensitising policy makers and civil society representatives by advocating for fairer representation.

However, learning content insufficiently and superficially representative of marginalised groups. This was elucidated by a civil society representative in DARE-RC’s Punjab Inclusivity workshop in 2024, who said that textbooks include arbitrary mention of marginalised communities and stop short of depicting social interactions across groups, for instance, between Muslims and followers of other religions, or between abled and differently abled persons. This critique holds for General Knowledge curriculum which poorly features content on multi-religious groups, their places of worship and festivities. We also see mentions of notable figures who belonged to marginalised groups, although inadequately as part of mere lists of heroes who fought for the struggle for Pakistan, and lists of national women leaders, among others.

Gender Bias in Assigning Roles

Another form of bias is based on gender discrimination. While there has been some improvement in the mention of female characters in textbooks, bias is present in how gender roles are assigned to characters. Mathematics and Science subject books need to embed more content which associates and includes female names in word problems to a larger extent than is currently seen. Language textbooks feature pictures of girls for verbs like ‘sitting’, ‘smelling’ while verbs like ‘skipping’ and kicking’ are reserved for boys. Girls are shown to be morally upright while naughtiness is reserved for boys, limiting possibilities for both boys and girls. This contributes to creating an imbalanced self-image for a child in terms of the ability to make morally upright choices, characterised by low expectations for boys and high expectations for girls that may increase feelings of guilt for girls when they are unable to meet these high standards. Similarly, characters from rural areas are depicted to be simple-minded and out-of-touch from the world outside.

Belongingness comes where you can be yourself. Transgenders don’t seem to belong at home, or at school. There is an environment-based dysphoria.

– Dr Sadya Salar, Sexually Transmitted Illnesses Specialist, Khwaja Sira Society, Lahore, Punjab.

Participants at the DARE-RC Inclusivity Workshop

Improving the Textbook Review Process

Government departments and provincial textbook boards have initiated steps towards inclusive textbooks by making the review process more inclusive through the addition of a sub-committee of experts from diverse religions in the review process. This was initiated in the Punjab province in 2023. The extent to which this group provided input and how well their feedback was incorporated in the proposed manuscripts remains unclear. However, the inclusion of diverse religious leaders is progress in the right direction.

Inclusive curriculum should be developed by engaging stakeholders from all marginalised groups whose inputs are important for forming implementation and policy for school curriculum.

– Muhammad Ayub, Advocate, Peshawar

| Subnational Discussions on Inclusivity in Education |

| The views presented here are based on insights gathered through the DARE-RC Inclusivity workshops organised across Pakistan in Balochistan, Sindh, Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Gilgit Baltistan. Workshops involved consultative discussions with persons with disability activists, diverse faith activists, transgender rights activists, academics/researchers, textbook board representatives, lawyers, human rights experts, gender-based violence experts, health experts, and civil society organisations representatives. |

Inclusive Textbooks Improve Children’s Growth

Textbook authors struggle with incorporating a range of criteria within content knowledge: the product must be child-centred, SLO- based, relevant, pegged at the appropriate level for the grade level, has graphics to aid learning, and includes assessment tasks. The additional requirement to also make it inclusive may raise the question: Is it worth the effort, and are the textbooks not already inclusive enough?

CWD and transgender children will benefit from a sensitive and integrated treatment of disabilities and gender in the content taught in schools, and children from diverse faiths and ethnicities will experience acceptance when they see names like theirs in schoolbooks — but how will such content provide an avenue for children’s growth whose experiences are not in the margins?

Acceptance of PWDs and marginalised groups as complete human beings capable of social and economic contribution should be introduced at schools at a very basic level through curriculum or social interactions.

– Sanaa Ahmed, Programme Manager, Society for the Advancement of Education (SAHE)

Participants at the DARE-RC Inclusivity Workshop

- Learning About Diversity

Through inclusive textbooks, all children may be expected to become aware of and learn about individuals and communities different than themselves. Early exposure to a range of ethnicities, religions, cultures and other forms of diversity is important for children to thrive in and contribute towards multi-cultural communities.

- Teaching Compassion and Harmony

Participants at the DARE-RC Sindh Inclusivity workshop highlighted how children sharing classrooms with a child with Down Syndrome take on a protective role, especially during playground activities. In contrast lies an ‘othering’ of differently-abled individuals, leading to dehumanisation and possible violence. Diverse exposure at school will broaden children’s perspective on who they consider to be their ín-group, developing positive perceptions and acceptance of people different than them. This will lead to compassion and unity amongst diversity, resulting in good citizenship. When integrating CWDs, transgenders, and other marginalised children into formal education, inclusive textbooks are a ubiquitous means of creating a more harmonious society.

- Breaking Stereotypes

By doing away with stereotypical representations, textbooks can expand possibilities for everyone. These stereotypes may be age or gender based, for example, celebrating male heroes in a humane light will allow boys to accept their feelings and nurture their emotional intelligence, and showing female characters being naughty or errant instead of pristine and infallible will help girls to develop realistic self-perceptions. Depicting a CWD as a problem solver rather than a recipient of compassion will do wonders for the self-esteem of CWDs and inspire other children to realise their full potential.

For a more inclusive community, the first step is a change in attitudes and knowledge; then, the system can support the change.

– Aqeel Bashir, REEDs Foundation, RYK

- Teaching the Teacher

Inclusive textbooks may guide the teacher’s behaviour in a more nurturing direction, overriding some biases by inviting him/her to reflect. Many teachers struggle with basic subject knowledge and may not be expected to learn about various genders, ethnicities, and faiths. An activist from the Sikh community in the DARE-RC Balochistan Inclusivity workshop shared how his teacher instructed him to remove his steel bangle ‘kara’ since the teacher was not aware of its spiritual significance in the Sikh faith. Such incidents would be minimised by textbooks which created a more sensitive and accepting ethos.

- Teaching at the Right Level

During all the Inclusivity workshops (except Punjab), participants averred the need for an inclusive curriculum for all students that included targeted strategies to address learners’ varying needs. Inclusive content should be integrated to address the learning needs of all students not performing at the class level. Introducing supplementary reading material to bridge learning gaps while teaching at the right level will benefit children who are struggling due to factors like not comprehending the content, not following the language of instruction, working as labourers, or not having educated parents for guidance.

- Demand-Based Learning

Textbooks that are current in their knowledge and updated according to the changing world will prepare learners to inhabit that world. An academic from the Balochistan Inclusivity workshop expressed that learning content should encompass current socio-economic and technological knowledge, for example about high-tech professions required for mass infrastructural developments, such as China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

- A Tool for Human Development

Inclusive textbooks will improve the emotional health of users, benefitting the larger community. Such textbooks will help learners from diverse backgrounds develop a positive self-image and fulfil their need for recognition. Such learning content will also help the class fellows of learners from marginalised communities to accept them and celebrate their uniqueness, fulfilling each group’s need for affiliation.

Inclusion is a cross-cutting theme in the DARE-RC project and one of the four key pillars of its research agenda: What works to improve drivers of learning for marginalised children in Pakistan? Click here to learn more about DARE-RC’s research priorities and areas.

—

Author: Ayesha Fazlur Rahman (Inclusivity Lead, DARE-RC)

Editor: Maryam Beg Mirza (Assistant Consultant, Education at OPM)

Media Communications: Farhad Jarral (Communications Lead, DARE-RC)Quality Assurance: Dr Sahar Shah (Senior Research Manager, DARE-RC)

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.

Researchers in the field may find themselves faced with an ethical responsibility: to respond if they gain knowledge of or witness direct harm to participants. The likelihood of such an instance is higher when conducting field work among vulnerable communities. Data and Research in Education – Research Consortium (DARE-RC) supports its research teams to be aware of and ready to respond to such challenges.

As part of the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) funded DARE-RC programme, several consortium-led and grant funded research studies are being commissioned in various parts of Pakistan. Research teams have been mobilised across all four provinces of Pakistan (Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and Sindh) as well as Gilgit Baltistan. Undertaking field research requires sensitivities to navigate and investigate within diverse communities across the country and necessitates having robust safeguarding policies and protocols in place to ensure no harm is done to participants.

All research teams are expected to follow stringent safeguarding requirements, such as going through the DARE-RC Safeguarding Training to ensure our presence, work and personnel are not causing harm, especially to children and vulnerable adults. Researchers are also obliged to be mindful of the power imbalance regarding the community or individuals in which they are engaging with including factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion and education background, etc.

| What do we mean by ‘safeguarding’? Safeguardingmeans taking all reasonable steps to prevent harm occurring to others as a result of the work that we do, promoting the welfare of vulnerable people, and protecting those who are at risk from harm. Vulnerable people typicallyinclude children and young people under the age of 18, and any person who may be considered vulnerable because of their age, a physical or mental disability or due to other circumstances. See Oxford Policy Management ‘s (OPM) Policy on Safeguarding of Vulnerable Persons to learn more about OPM and DARE-RC’s approach to safe and ethical research practices. |

The aim is to prevent all forms of harm from occurring in the first place. Safeguarding measures also work to ensure that a victim/survivor-centred approach is taken whereby proper response and action measures are executed when incidents do arise or come to our attention.

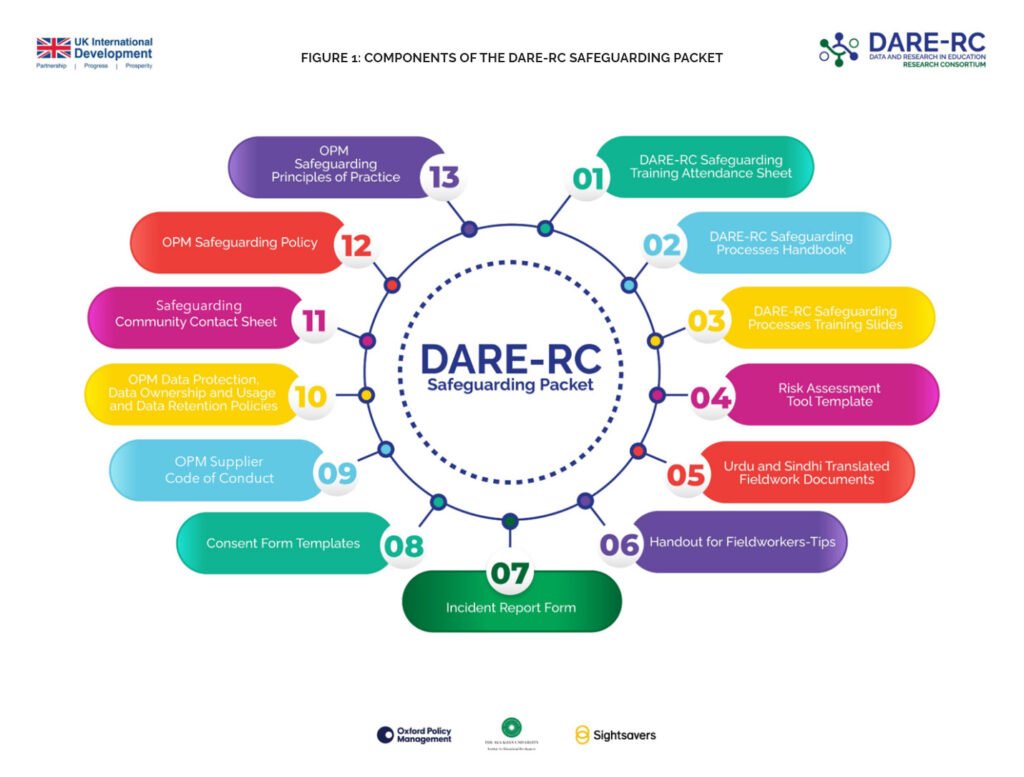

What is Included in DARE-RC’s Safeguarding Training Packet?

The Safeguarding Packet is made up of several relevant OPM standard policies, the DARE-RC Safeguarding Handbook, DARE-RC Safeguarding Training slides, various key fieldwork resources (i.e. consent forms, tips for fieldworkers, safeguarding community contact sheet, and incident report form), the Risk Assessment Tool template and other materials. It is expected that all research and data collection personnel review these documents prior to commencing fieldwork.

Consent Is Key

For ethical purposes, it is essential that all participants provide consent prior to being interviewed or included in a research study. The consent forms must use accessible and sensitive language and cater to the specific target population. In the case of young children and individuals with lower literacy levels, verbal assent can be obtained as well. It is important to note, while confidentiality is fundamental, it does not override our duty to protect the participants in case of any reported misconduct.

How to Handle Incidents?

While in the field, we may be trusted by vulnerable people with information related to incidents of harm, abuse or neglect that they feel can be brought to our attention which may not be directly related to our work. Instead, we come to know about them by virtue of our presence in the community. We may even witness harm done to children or vulnerable adults during fieldwork or hear about/witness harm done by a fellow colleague. How do we, as researchers, respond in the face of such incidents? Listening attentively without judgement, logging relevant information in the incident report form and following the incident reporting procedures without taking matters into our own hands is important for the safety and wellbeing of the researchers, individuals reporting incidents and the respective victim(s).

Not only do we have a moral obligation to report incidents of harm, but we also have a contractual obligation to do so. Ultimately, our work aims to improve lives. Safeguarding is our responsibility considering that vulnerable people do not always have the power or skills to protect themselves.

Furthermore, DARE-RC has developed a Support and Referral Network in Pakistan that we may utilise when needed. It is made up of NGOs and government entities working on human rights, child protection and women’s rights issues providing awareness, legal and psychosocial support as well as shelter facilities.

Want to Learn More?

Numerous global resources and standards are available for organisations working in the humanitarian, aid and development sectors. A few include Keeping Children Safe, the Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub and the CHS Alliance.

Keeping Children Safe sets International Child Safeguarding Standards (The International Child Safeguarding Standards – Keeping Children Safe) to help organisations protect children from abuse. One of the requirements for all research teams working under DARE-RC is to complete the Risk Assessment Tool developed by KCS to identify potential risks (i.e. regarding cultural norms, data collection, questionnaire design, data protection, staff, etc.) to vulnerable people related to our work and develop mitigation strategies to address them.

Additionally, the Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub (Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub) is a programme that aims to strengthen safeguarding policies and practices against Sexual Exploitation, Abuse and Sexual Harassment (SEAH) of organisations working in the aid sector. A valuable resource they provide is a safeguarding training which is available in several languages to enhance accessibility. The CHS Alliance (CHS Alliance), a global alliance of humanitarian and development organisations committed to making aid work better for people, is leading an initiative funded by FCDO called the SEAH Harmonised Reporting Scheme (alongside the Steering Committee for Humanitarian Action). This aims to increase reporting of incidents by supporting NGOs and private sector organisations in collecting and reporting SEAH incidents in a more uniform way. It is currently being piloted. From April 2024 – September 2024, 178 incidents were reported by the SEAH Harmonised Reporting Scheme (HRS) participating organisations with 63% of incidents being against aid recipients and their communities and 37% of incidents against staff members.

Taken From: SEAH HARMONISED REPORTING SCHEME (HRS): Insights on Sexual Exploitation, Abuse & Harassment (SEAH) incidents against aid recipients and their community.

Ultimately, the goal behind safe and ethical research practices is to treat individuals and communities with dignity and respect and particularly promote the welfare of vulnerable people by putting them at the centre of our programme design and implementation.

Click here to learn more about DARE-RC’s research priorities and areas.

–

Authors: Jasmine Abraham (Former – Consultant, Education at OPM) and Dr Monazza Aslam (Research Director, DARE-RC)

Editor: Maryam Beg Mirza (Assistant Consultant, Education at OPM)

Designer: Farhad Jarral (Communications Lead, DARE-RC).

Quality Assurance: Dr Sahar Shah (Research Manager, DARE-RC)

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.

Schools and communities are on the frontline of the climate crisis in Pakistan. Floods, drought and heat waves impact children’s learning, with schools closing when disaster strikes. The absence of support and encouragement from the government to identify and build on local strengths and experiences has emerged in a DARE-RC study in schools in Islamabad, Punjab and Sindh; highlighting the need to ensure this relevant experience and knowledge is not overlooked. This study focuses on generating contextually grounded evidence on what resilient education means for adolescents, their teachers, education authorities and communities in Pakistan.

Community-led insights

In an era marked by unprecedented global challenges, the impact of climate change on local communities and the resilience of education systems to cope has become an area of critical focus. Education is vital for enhancing our ability to mitigate and adapt to these changes. The climate crisis requires that we – as education researchers, practitioners, and decision-makers critically evaluate and improve policies to ensure resilient, inclusive education for all. Past solutions may no longer be effective, necessitating more ambitious and comprehensive approaches to adapt and mitigate the effects of climate change on education systems and communities.

To address the climate crisis within the shrinking window for action, we need to radically transform education systems to change mindsets and paradigms that go beyond broad, general principles and consider local contexts and lived experiences. Community-led insights are key to driving these changes and to shaping policy frameworks.

In recent years, the importance of community-led insights in shaping policy frameworks has gained significant recognition. Communities on the frontline of climate impacts have the most intimate understanding of their vulnerabilities, making them best suited to design and implement practical, sustainable, and inclusive solutions. Similarly, community-led climate and education actions lead to significant improvements in education quality and accountability. By placing citizens at the core of decision-making, policies are more reflective of the true needs and aspirations of the community.

Hence, we need schools and local communities to be the focal point for local adaptation to the climate crisis, with students and community members empowered to play significant roles in decisions that directly influence their lives. Building on people’s lived experiences and how they relate to climate change is crucial – not only for more effective policy development, but also for finding solutions that do not exacerbate existing inequalities.

Policies that fail to account for local contexts and vulnerabilities have been documented to be ineffective or even harmful, undermining efforts to address climate change. For example, Pakistan’s National Water Policy (2018) and large-scale water management project that prioritises centralised irrigation systems have been criticised for not adequately addressing the needs of small-scale framers and the unique hydrological conditions of specific regions. Community-led insights are crucial for driving climate policy change and creating more effective and equitable solutions, resulting in long-term sustainability.

Involving schools and communities

Effective climate action is not just about political and policy decisions. It is also about behavioural change at community and individual level. And education is not just about the right policies and curriculum, nor it is confined to the walls of a classroom: it is a collective effort involving teachers, students, families, and the broader community.

Communities and schools play a pivotal role in maintaining robust, adaptable, and resilient education services. As community hubs, schools can promote collaboration, equity, and shared responsibility, ensuring learning continues during extreme climate and environmental events.

Building resilient education systems presents several challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities, affecting over 1.6 billion learners globally. Key challenges include ensuring equitable access to education, especially in low and lower-middle-income countries, and developing effective hybrid learning systems. Individual actions matter: by adopting sustainable practices like reducing energy consumption, choosing sustainable products, supporting green infrastructure in school and advocating for climate action at local level students can contribute to a more resilient future.

Bridging local solutions and system-level reforms

Most climate adaptation planning still occurs at the international and national levels, with local institutions and actors participating on the margins as beneficiaries rather than as agents of change. This gap in participation is a major cause for ineffective policy implementation for system change and persists despite considerable efforts to develop new approaches.

To help bridge this gap, several approaches can be employed. One is the use of participatory community-level multisectoral collaboration sustained beyond individual projects. Evidence shows that community-level participatory (or bottom-up) initiatives in agenda setting, service design, delivery, and systems strengthening can lead to policy adaptation (see Ding et al., 2023 and Suarai et al., 2024 for more evidence). Shifting from traditional top-down approaches fosters ownership and inclusivity, empowering communities with greater agency. This results in policy adaptations in line with the local setting (see Rahaman et al., 2023). In this approach, context, power equality, and parity in voice and agency matter. Implementation involves collaborative bargaining rather than the explicit control of higher-level decision makers.

Since the impacts of climate change on education are experienced at the local level first, employing a bottom-up approach gives us a better understanding of people’s contextual realities and better supports sustainable system reform.

Resilience begins with local voices

Addressing the climate crisis demands a radical transformation of our education systems to foster resilience and adaptability. This transformation should be driven by community-led insights and participatory approaches that bridge the gap between local solutions and system-level reforms, leading to policy changes that are more inclusive, equitable, and responsive to local needs.

Generating evidence on lived experiences and how they relate to climate change is fundamental for effective policy development and implementation. Failure to put the lived experiences and perspectives of learners and local communities at the core of decision-making processes will result in policies that do not reflect the true needs and aspirations of the community.

The urgency of the climate crisis demands ambitious solutions that go beyond traditional policies and programmes. By exploring how schools and communities can develop agency and be supported to create effective solutions to address local needs, researchers and policymakers can help make sure education remains a powerful tool for mitigating and adapting to global challenges.

Resilient education service delivery is one of the four key pillars of DARE-RC’s research agenda: What works to develop continuity of resilient education service delivery through improving systems coherence? Click here to learn more about DARE-RC’s research priorities and areas.

–

Author: Dr Sapana Basnet (Senior Research Associate, Sightsavers & Thematic Lead, DARE-RC)

Copy-Editor: Maryam Beg Mirza (Assistant Consultant, Education at OPM)

Quality Assurance: Dr Sahar Shah (Research Manager, DARE-RC)

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.

This blog was written by Ha Yeon Kim, Senior Advisor, and Monazza Aslam, Research Director, Data and Research in Education Research Consortium (DARE-RC) in Pakistan.

Pakistan just has become the ground zero for one of the world’s largest public school outsourcing experiments. In three phases, the Government of Punjab plans to transfer nearly 14,000 public schools—approximately 30% of all its schools—to NGOs and private operators via Punjab Education Foundation (PEF). This bold initiative aims to fix the broken education system, riddled with a long list of problems, including inefficient school management, poor infrastructure, outdated curricula, teacher shortages, millions of out-of-school children, and poor learning outcomes.

But can this bold move deliver on its promises? The stakes are high, and so are the concerns. Critics have warned of hidden costs, potential decline in quality due to cost-cutting measures, lack of accountability and oversight, and risk of exclusion of the most marginalised populations and communities.

Whilst Pakistan has a long history of engaging in different types of public-private partnership (PPP) arrangements, the sheer scale of outsourcing in Punjab is unprecedented. The evidence to back such reform at a staggering scale is, at best, limited. Globally, research on outsourcing public schools—typically where a private provider takes over the management of a government school—shows inconsistent impacts. For example, Liberia’s school outsourcing experiment improved student learning outcomes but came at the cost of excluding marginalised groups like more disadvantaged girls and students from overcrowded schools. It also exceeded the projected per-pupil budget by more than double.

Closer to home, there are very few available high quality studies that examine the direct impacts of this type of PPP arrangement. The handful of studies that do exist have shown no significant improvements in student learning outcomes. Similarly, research on various other forms of PPP in Pakistan—including school subsidies, school vouchers, and new schools in marginalised communities—has shown modest impacts in increasing access in certain cases, with little to no effects elsewhere.

The presumed advantage of private school management also seems uncertain. Research on the “private school premium” in Pakistan has shown that the quality of education in private schools wildly varies, and so does the added value of private schooling on student outcomes. Given the scale of Punjab’s outsourcing policy, this variability is likely to be amplified, posing a critical challenge: ensuring consistent quality across thousands of schools managed by diverse operators.

What will it take for success?

To make this ambitious reform work at scale, Punjab must address key challenges from the outset. Based on existing evidence, the following would be important considerations for the PEF and the Punjab government:

- Equity is not optional. Robust safeguards must be built into contracts as well as in the monitoring and evaluation process to protect marginalised groups. This could include guaranteed enrolment quotas for underserved communities and targeted support for marginalised children.

- Cost expectations should be realistic. Quality education does not come cheap, and achieving efficiency takes time. Both Liberia’s experience and early Punjab data show expenses exceeding projections. Budgeting for 150-200% of the initial estimates, at least for the first year, may be necessary.

- Active oversight is key. Outsourcing does not mean hands-off. Proactive oversight and monitoring to enforce the minimum quality standards and safeguards are requirements, not an option.

- Transparency trumps expediency. Transparent bidding processes, equitable school selection criteria, and financial accountability measures are critical for maintaining public trust—especially for such large-scale privatisation efforts.

- Standardisation matters. Private operators must align with public school curricula and standards. Misalignment could result in poor outcomes, with teachers and students bearing the brunt. The government must ensure that curricular standards are met and that teachers are well-qualified and adequately trained.

- Communities must be engaged. Building trust with local communities is vital. Operators should involve teachers, parents, and local leaders in decision-making processes to foster ownership and support.

A path forward for Punjab

Punjab’s school outsourcing policy is a bold attempt to transform its struggling education system through innovation and public-private collaboration. While the initiative holds promise—particularly for increasing access—it also carries significant risks, especially for marginalised children and communities often overlooked in large-scale reforms.

To succeed, policymakers must adopt a proactive approach that prioritises equity and inclusion, ensures rigorous oversight to uphold quality, and actively engages stakeholders, including marginalised communities. Private operators must be held accountable not only for outcomes but also for their efforts to reach and serve the most vulnerable populations.

This is more than an experiment—it is an opportunity to redefine education delivery in Pakistan. By learning from global experiences and tailoring solutions to its unique context, Punjab can set an example for others facing similar challenges. Success will hinge on thoughtful and inclusive execution, requiring commitment from both private operators and policymakers to ensure no child is left behind in this transformation.

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.