Government Primary School, Chiniot

What if boosting school attendance was as simple as sending a text? Or if improving student performance required simply sending a friendly reminder about an upcoming test? Thanks to behavioural science insights, short, well-timed nudges have been remarkably effective in addressing education related problems from South Africa to Chicago.

Behavioural science, which explores why people act the way they do, shows us that tiny changes – e.g. in how information and choices are presented can lead to big improvements. Rather than focusing only on building new schools or buying technology, behavioural science digs deeper into everyday habits, motivations, and mental shortcuts that shape how students, parents, teachers and school administrators behave.

In education, this means creating smart interventions that boost engagement, support learning, and encourage positive habits both inside and outside the classroom. In this blog, we look into how behavioural science is transforming education across the globe, and what it could mean for developing countries like Pakistan, where education systems face serious barriers but also hold enormous potential.

Behavioural Science Frameworks: Why They Matter

Behavioural science interventions work because they target the small psychological factors that shape how people act. Instead of relying on guesswork, we use structured ways to identify what really drives or stops a behaviour.

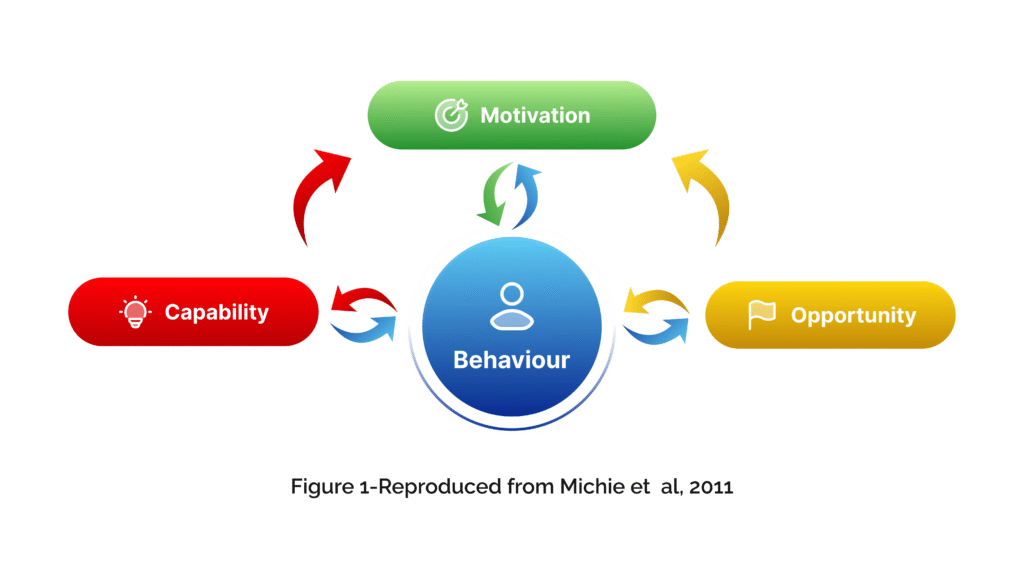

One useful framework, known as the COM-B model, explores a person’s capability and opportunity to perform an action, and the motivation to follow through, when determining how that behaviour can be influenced.

For instance, a parent may want her child to make positive food choices, but a simple reminder, like a short text message, can help the child select a healthier option for school lunch. Behavioural science approaches, such as designing small nudges or using positive social cues, follow the same principle: small changes in the way choices are presented can lead to better choices being selected. By diagnosing behavioural barriers via such frameworks, designers ensure interventions tackle specific limitations instead of relying on guesswork.

Motivating Students

Sometimes it’s not about how much you reward effort, but when and how you do it. A fascinating experiment in Chicago Public Schools tested whether behavioural science could help students perform better in exams. Students were given a monetary reward before the test, with one condition: it would be taken away if they underperformed. This small change in framing made all the difference. Those who faced a possible loss improved their scores by 0.12 to 0.22 standard deviations compared to students who were promised the same reward later. The takeaway is that timing and framing matter more than the size of the incentive. Immediate conditional rewards use present bias and loss aversion to motivate students who might otherwise struggle to stay focused on long term goals.

These insights are not limited to students. In many low resource classrooms, teacher motivation plays an equally critical role. Studies show that recognising teachers for effort and purpose, rather than simply offering financial incentives, can shift attitudes, reduce absenteeism, and improve student outcomes. Small and timely feedback loops build meaning and accountability, helping teachers reconnect with why they teach.

Enhancing Parent Involvement

A gentle reminder can go a long way. In South Africa’s Western Cape, local authorities tested a simple idea: sending parents short, personalised messages when their child failed to show up at an after-school centre. The messages were friendly and non-punitive, no fines, no warnings, just a prompt that said, “Your child was absent today.” Attendance rose by 39%. The power was not in technology but in empathy.

The messages made parents feel seen and involved, turning awareness into action.

In Malawi, Dizon Ross (2019) found that when parents were clearly told how their children were performing through simple, verbal explanations, they updated their beliefs and directed time and money more effectively. Parents who understood where their children stood academically became more strategic and supportive at home.

In the United States, Bergman (2016) showed how regular text updates can transform parental engagement. Parents received weekly SMS messages about missed assignments, attendance, and grades. With this timely information, course failures dropped by 28% and attendance improved. The messages did not reveal anything new – they just made important details more visible and actionable. For many busy parents, this was the difference between being disconnected and being empowered.

Castleman and Page (2015) found similar results in early education. Their pre-kindergarten text campaign sent parents small, actionable prompts like “Read one letter in your child’s name tonight.” These micro reminders improved literacy interactions and produced learning gains equal to two or three extra months of schooling. Later, Bergman et all. (2019) showed that parents who received regular updates about missed work and low GPAs were more engaged not only with attendance but also with school meetings and follow ups. Across both studies, the insight was simple, timely and clear communication helps parents take small steps that add up to big changes.

Aligning Teachers and Parents

While parent focused nudges often work well on their own, they become even more powerful when teachers are part of the loop. UNICEF lessons from Côte d’Ivoire found that messages sent only to parents boosted attendance, but adding teacher reminders created an extra effect. This suggests that student learning thrives most when parents and teachers act together, reinforcing each other’s roles rather than working in isolation.

Taken together, these examples show that behavioural science is not about expensive technology or sweeping reforms. It is about understanding how people think and feel and designing interventions that fit that reality. Small, timely, and empathetic actions can create meaningful shifts in behaviour, helping students learn better, parents stay engaged, and teachers stay inspired.

How could this play out in Pakistan?

In South Asia, behavioural science is quietly shaping the way we think about change. From health to education, organisations are beginning to realise that information alone is not enough. How we deliver it, and when, matters just as much.

UNICEF, for instance, has started introducing workshops across the region to help teams use behavioural insights in their programmes, aiming to improve outcomes in health, education, and nutrition. These efforts focus on understanding how social norms and gentle nudges can help people make better decisions in their everyday lives.

To date, many of application of behavioural science interventions in South Asia have focused on public health. In Sri Lanka, Olupeliyawa et al. (2008) explored how behavioural science could be integrated into medical education, showing how appropriate nudges could enhance communication skills and professionalism among future doctors. In India, a similar 2013 study highlighted the role of behavioural science in helping medical students understand social determinants of health and build empathy with patients. These examples show how behaviour-focused thinking can humanise systems that often rely only on technical fixes.

In Pakistan, applying behavioural science to education is still new but promising. A recent FCDO funded campaign, Aaj Kiya Seekha, used a behavioural framework to encourage parents to engage more actively in their children’s learning at home. The Learning and Educational Achievement in Pakistan Schools (LEAPS) project has also tested simple, low -cost interventions like report cards and parental engagement tools in rural Punjab with encouraging results.

Other studies, such as York et al. (2017) and Burgman (2015), point to the power of technology -based nudges like automated calls or SMS reminders to support education programmes. These digital prompts can make learning feel more personal and consistent, but their impact depends heavily on trust and cultural fit. A message that feels unfamiliar or impersonal can easily lose its influence, especially in close knit communities.

Let’s break down how these interventions can be used in this context.

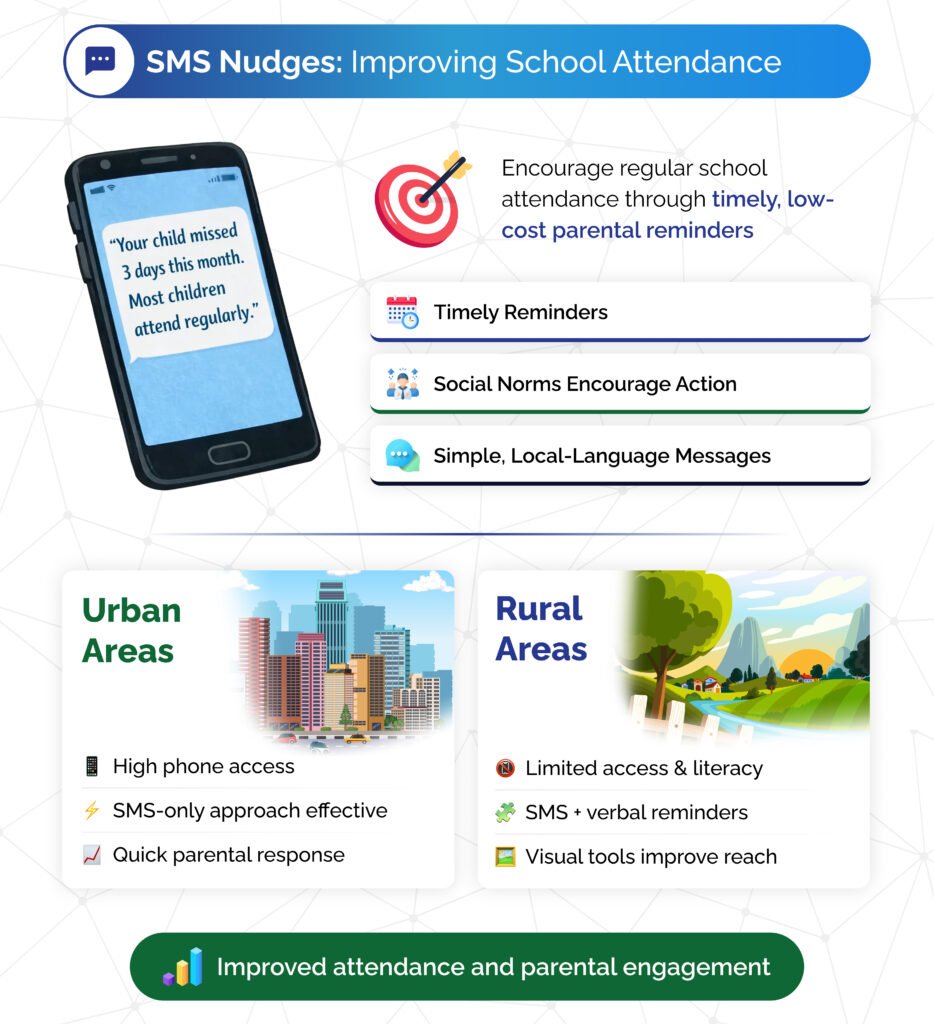

- SMS nudges: Take a simple text message. Short, local-language messages like “Your child missed 3 days this month, most children attend regularly” can boost attendance, especially in urban areas with better phone access. These messages use social norms and timely reminders to nudge parents into action. In rural areas, where access and literacy are lower, these SMS nudges could be paired with verbal or visual tools to reach everyone effectively.

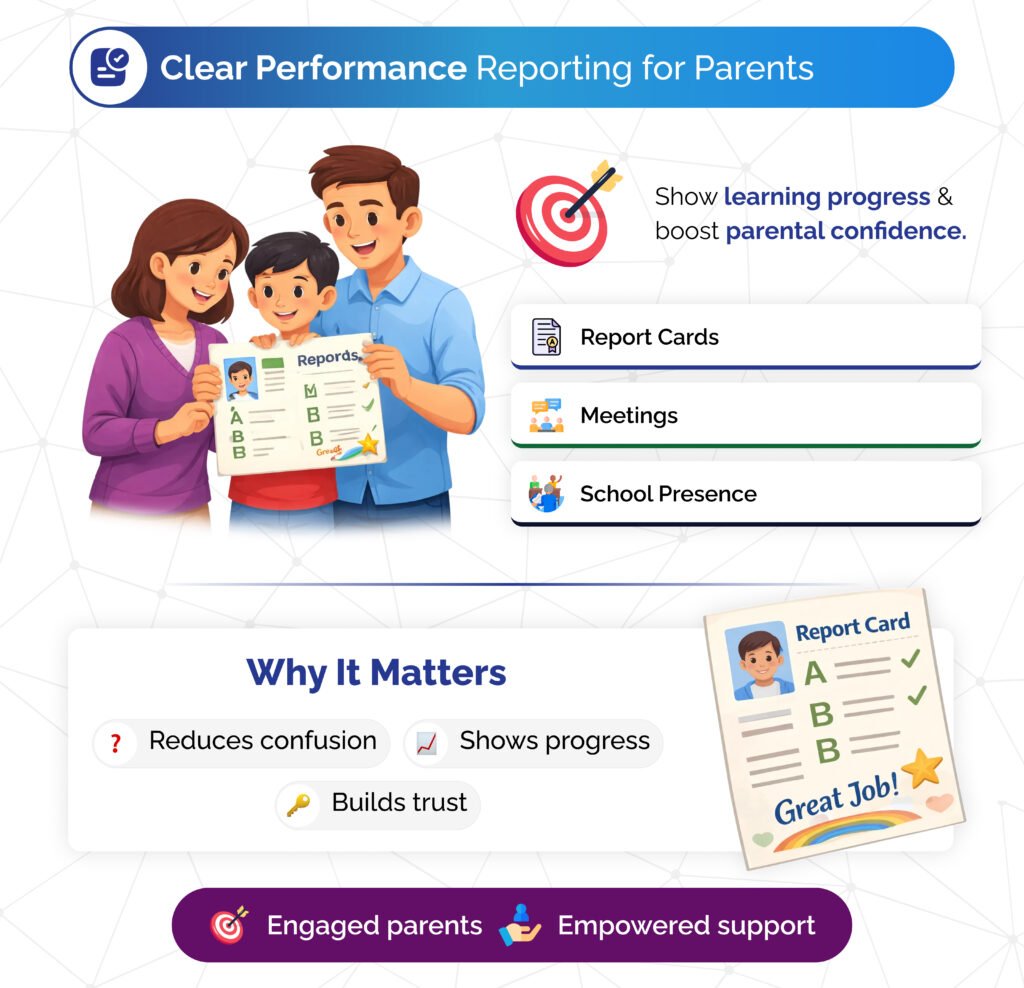

- Clear performance reporting: Sometimes, seeing progress is just as motivating as a nudge for parents. Simple report cards, increased parent-teacher meetings and community presence of the schools help parents understand their child’s learning and encourage them to support education at home. Parents often feel disconnected and overwhelmed from their child’s schooling. Feedback builds confidence, trust, and engagement, helping parents to feel empowered to help rather than overwhelmed.

- Small, timed rewards for students: In exam-focused contexts like Pakistan’s matriculation system, giving students small, immediate incentives like praise certificates handed out in advance but kept only if effort is sustained, can motivate them to focus. This uses loss aversion to combat present bias, where short-term comfort often wins over long-term goals.

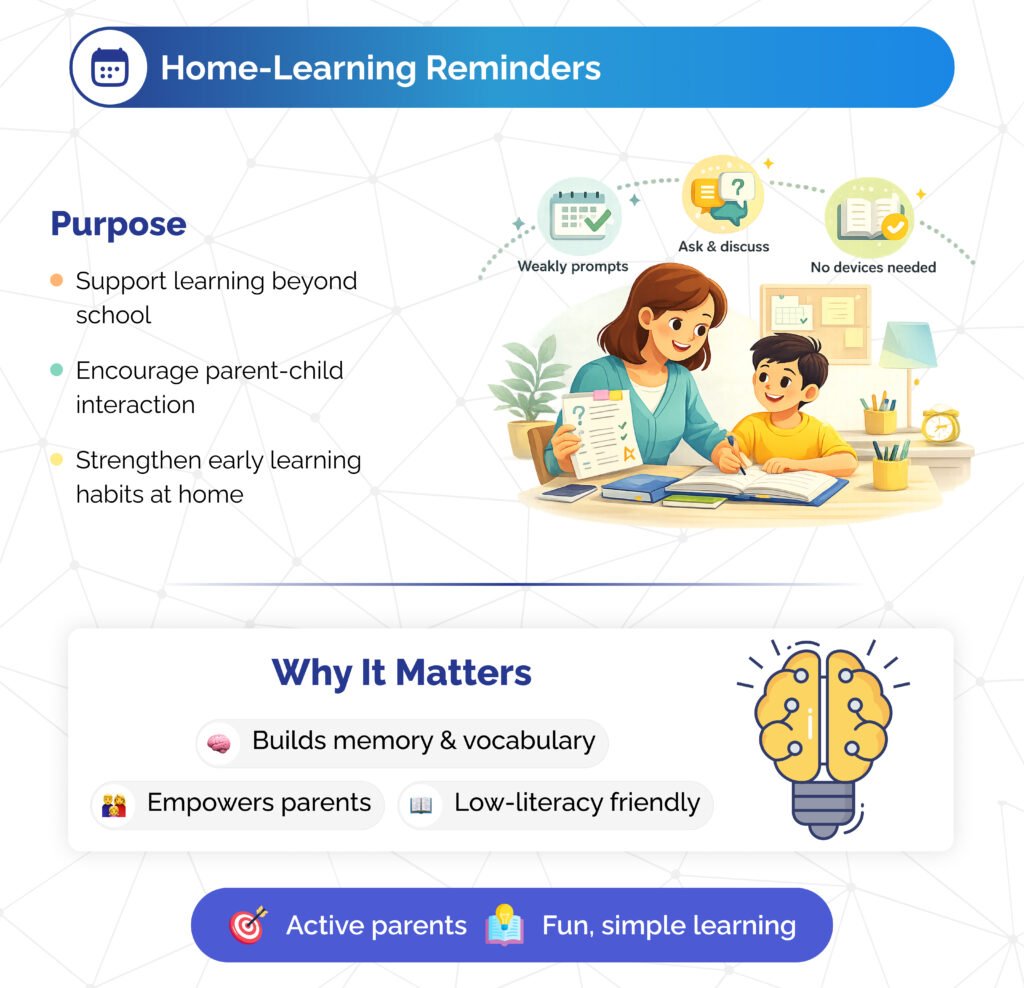

- Home-learning reminders: For younger kids, simple activity-based messages sent to parents can support learning outside the classroom. For example, weekly prompts like “Ask your child to name 3 things they saw on the way home” help build vocabulary and memory. These nudges don’t require devices and empower parents to be active participants, even in low-literacy settings.

Behavioural science reminds us that people don’t always make perfectly logical choices, especially when facing poverty, stress, or uncertainty. By designing interventions that fit local realities, testing them, and adapting accordingly, Pakistan’s education system can become fairer, more effective, and better at reaching those who need it most.

Lessons from the Field

A recent DARE-RC study in District Chiniot, Punjab aims to test the application of behavioural science interventions in reducing dropout rates between classes 5 and 6. It also examines whether frameworks like the COM-B can yield useful insights in Pakistan, despite being developed and validated in the West. Although in early stages, the study has already provided valuable insights into the application of COM-B, and the decision matrix that pre-empts parents’ enrolment decisions:

- Contextualising data collection using interpretive methods: When low-literacy rural parents were asked to respond to statements using a 1 to 5 scale, from strongly agree to strongly disagree, many found it confusing. Some selected only the first or last option, while others relied on what they thought the enumerator wanted to hear. This did not mean they lacked opinions, but rather that the format did not align with their preferred way of expressing themselves. Numeric scales often feel abstract or distant from everyday language, making it harder to capture genuine responses. The research team thus developed an interpretive matrix, translating gestures, expressions and intonation as used by parents who were largely unable to read or write. This matrix was used by field staff to code responses into a Likert-type scale, amendable to statistical analysis.

- Effective utilisation of the COM-B framework to integrate evidence for intervention development: Application of the COM-B framework highlighted high parental motivation for continuing children’s education, but low capability and opportunity to carry out the enrolment process, suggesting that interventions that aimed to increase capability and opportunity could improve enrolment outcomes.

- Distinctive underlying factor composition in the Chiniot dataset: Exploratory factor analysis to uncover latent patterns in the data showed that other scales appeared to be manifest more strongly than they did in Western applications. These included parental support skills – capturing parents’ ability to actively engage with and support their child’s education, and financial responsibility – representing parents’ perceived ability and commitment to financially support their child’s education. Rather than distinct capability, opportunity, and motivation components, we found integrated factors that combined elements across these dimensions.

Conclusion

Behavioural science is powerful because it helps explain why people act the way they do. But in Pakistan’s rural context, it must go employ creative approaches to channel the localised context and capture cultural nuance. In so doing, behavioural science can help design practical, inclusive solutions that reflect how people really think, decide, and live.

The evidence is unequivocal – behavioural science gives us a fresh approach to solving education problems by understanding why students, parents and teachers make certain choices. It helps us see the mix of emotions, skills, and perceptions that shape these decisions. When paired with simple digital tools – such as SMS, phone calls, or app-based reminders – these insights can make interventions scalable and affordable, while staying rooted in local realities.

Authors: Khadija Hammad (Communications associate, Middle School Transition Project, DARE-RC), Ayaan Rauf (Intern, Middle School Transition Project, DARE-RC), and Dr. Zainab Latif (Thematic Lead, DARE-RC)

Quality Assurance: Dr. Sahar Shah (DARE-RC Senior Research Manager)