DARE-RC International Education Summit 2025

The International Education Summit in Islamabad, Pakistan (December 17-18, 2025) organized by DARE-RC brought together researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to share insights from projects aimed at improving access and learning outcomes for children across Pakistan. Grounded in evidence-based practice, presentations explored building resilient education systems, strengthening teaching quality and governance, and addressing the intersecting forms of exclusion that prevent children from reaching their educational potential. Our project contributed initial findings on scaling Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) in Pakistan’s Sindh province, which aligns with broader evidence on implementing effective practices at scale.

TaRL is a proven pedagogical approach that groups children by learning level rather than grade, providing targeted support through relevant materials and activities. Evidence from Pakistan demonstrates TaRL’s effectiveness in building foundational learning and life skills, particularly for out-of-school children and those who have reached primary grade 2 without mastering basic competencies. Beyond its effectiveness in remedial learning, the approach is also cost-effective. However, questions remain about whether provincial governments can scale TaRL successfully. Our DARE RC-funded project examines how the Government of Sindh is adopting, adapting, and implementing the TaRL intervention developed by Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (ITA), with specific focus on the enablers and barriers to scaling the approach across all government schools in the province.

In this blog, I reflect on a question central to our project: what does the evidence presented at the DARE-RC Summit 2025 reveal about TaRL’s potential to improve equitable learning at scale? I draw primarily on insights from scholars, practitioners, and policymakers, as well as notes from the presentations I attended. In the following section, I outline key aspects of our project alongside findings from other presentations that inform our understanding of scaling TaRL equitably.

Reflections on System-Level Processes

Preliminary findings from our project using key informant interviews with stakeholders from the School Education & Literacy Department (SELD), Government of Sindh, show that:

- TaRL approach is perceived to be embedded within foundational learning targets and policy focus on Early Childhood Education in Sindh.

- TaRL has demonstrated improvements on student foundational learning through remedial camps, particularly led by ITA.

- Teachers and headteachers trained in the approach have provided positive feedback.

- SELD shows strong political commitment to scaling the approach, especially through curriculum adaptations that enable differentiated learning levels in literacy (local language, Urdu, and English) and numeracy.

This final point is central, as it highlights the strong commitment, willingness, and partnership essential for policy uptake. At the Education Summit, we had the opportunity to discuss our project with Dr. Fouzia Khan, Chief Executive Advisor of Sindh’s School Education & Literacy Department, and we continue to benefit from her guidance and insights. We discussed key challenges stakeholders have identified in adapting TaRL, including aligning TaRL content design with the Government of Sindh’s established formats and procedures, and ensuring ongoing support from teachers and headteachers so the approach can be implemented effectively within existing school timetables and requirements.

The Education Summit yielded important lessons about the political economy of educational reform in Pakistan. Rafiullah Kakar’s presentation highlighted variations in state capacity to deliver services and the significant differences in learning outcomes between schools across districts. His research unpacked how power distribution within political settlements affects outcomes, even when resources are distributed equally. Dr. Farah Nadeem’s research on the digitalization of teacher professional development illuminated the gap between training and practice—specifically, the disconnect between teacher training content and the realities of multigrade, multilingual classrooms. This raised a key question for our project: would TaRL training face similar implementation challenges? Dr. Yasira Waqar’s presentation examined how technology can improve transparency and efficiency in teacher distribution while simultaneously creating unexpected shortages in remote rural and under-resourced schools. Given these provincial and regional variations, we must continue examining how teacher mobility is likely to impact TaRL’s effective implementation over time in Sindh.

Reflections about Exclusion and Equity

Sitting in the classroom and not being able to understand the lesson is a marker of exclusion. For our project, we collected learning assessment and sociodemographic data from 879 students in 57 schools in order to capture learning disparities for children in upper grades of primary school. Selected schools had teachers who were trained in the TaRL pedagogy and were committed to implement the remedial pedagogy as part of their regular practice for 60 days after training. Students and schools were selected from Karachi West (429 students in 29 schools) and Umerkot (449 students from 28 schools).

As discussed during the Education Summit, we were interested in using data that is relevant to the context in which we work. This means data that is meaningful for practitioners and policymakers. In terms of learning assessment data, we used the ASER Pakistan tool, with a small adaptation. Selected children were asked to complete the ASER tool from the start, from the most basic foundational skills such as being able to identify letters and numbers, to the highest level, reading a paragraph or successfully performing subtractions and divisions.

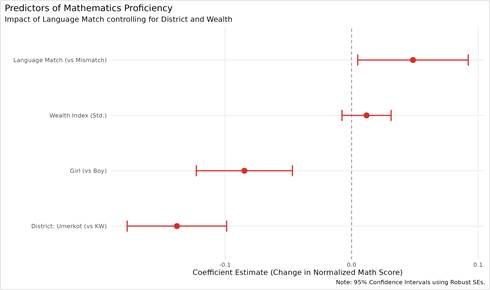

Figure 1 shows some of the inequalities in foundational numeracy. Among the key indicators of inequalities, we included learning in a language that is different to the one spoken at home, household wealth, gender and location. Results show that children who are learning in a language which is similar to the one spoken at home achieve higher scores in numeracy. For wealth, we did not find significant differences among those who live in relatively richer households, however for gender we found that boys outperform girls. Finally, children living in Umerkot underperformed relative to children living in Karachi West.

Figure 1: Predictors of Foundational Numeracy

Source: Numeracy Data from the ASER Tool

Dr. Nishat Riaz’s presentation offered a powerful reminder: exclusion is not born, it is built. Exclusion operates systematically—through factors like language of instruction—meaning scalable innovations must address root causes. For our project, this means focusing not only on existing regional disparities in learning, but critically on multiple intersecting dimensions such as language, disability, and gender. Dr. Riaz challenged researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to engage with existing data through diverse epistemic lenses and, as Dr. Rabea Malik emphasized, with the diagnostic capacity needed to build resilient systems. Pakistan’s education system generates substantial data, yet it remains difficult to access and therefore underutilized. As Dr. Laraib Niaz’s review explored, this underutilization prevents educational researchers in Pakistan from examining data that could inform policy-relevant questions and build system resilience.

Several presenters at the Education Summit highlighted how climate change is likely to amplify educational exclusion. Dr. Hadia Majid examined climate change’s impact on schools through flooding and exposure to hazards including heat, droughts, and poor air quality. Her research focused on mitigation strategies by schools, households, and district governments to provide greater protection as these risks intensify. Dr. Sapana Basnet’s research explored what resilient education means for adolescents with disabilities, particularly as human-made disasters like waste pollution disproportionately impact their health and wellbeing through waterborne diseases. Dr. Saher Asad used existing data to demonstrate how air pollution exposure affects cognitive ability, as measured by lower test scores. For our project, these findings are particularly relevant: TaRL will likely be scaled in crisis-affected areas. Embedding remedial practices into teaching from the outset may help mitigate some of the impacts identified by researchers at the Summit.

Reflections on Teachers and Practice

As I reflect on the important role of teachers, I would like to conclude with 5 key areas which are central to pedagogical practice, and which many of the DARE-RC funded projects are examining as part of their research:

- Pedagogy is institutionalized. Pedagogical approaches operate within the normative and material conditions of classrooms. They are therefore inseparable from teachers’ professional identities and must be examined within the actual conditions of teaching and learning, as demonstrated by Dr. Sadia Bhutta’s research on science and mathematics instruction.

- Pedagogy is interpersonal. It is grounded in relationships among all stakeholders—not only teachers and learners, but also leaders, inspectors, and parents. Dr. Zahra Mansoor’s research on parental engagement illuminates the barriers parents face in supporting their children’s education.

- Pedagogy must be understood socio-culturally and politically. Teaching practice occurs within specific historical moments and carries ideology, language, and traditions. It must be understood within its political economy and adapted to diverse sociocultural contexts, as reflected in Dr. Camilla Chaudhary’s research on school cultures and leadership, which examines how school leaders can enable transformative teaching practices.

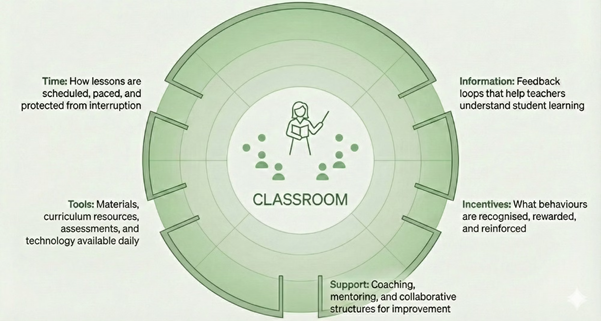

- Pedagogy should be theory-driven. Pedagogy provides the framework that orients and facilitates interactions, helping learners construct knowledge, develop understanding, build values, and engage in social interactions. Dr. Irfan Muzaffar offered insightful reflections on classroom realities and system possibilities in his session (see Figure 2).

- Pedagogy is intrapersonal. Teachers bring their own values, beliefs, and worldviews to the teaching and learning process. This personal dimension is central to understanding how teachers interpret curriculum and assessment, as discussed by Dr. Aliya Khalid.

Figure 2: The System Entering the Classroom Through 5 Doors

Source: Presentation by Professor Irfan Muzaffar (DARE-RC Education Summit 2025)

As we move into the next stage of our project on TaRL’s scalability in Sindh, we will draw on many lessons from the Education Summit, particularly as we engage with teachers and their adoption of this pedagogical approach. Importantly, we remain active participants in DARE-RC’s communities of practice, sharing knowledge and ensuring our research contributes to a collective approach rather than an isolated project. This collaborative engagement should strengthen how policy is informed by evidence from multiple perspectives while maintaining coherence across policy, regulation, and service delivery.