Adolescents in Pakistan Live in an Increasingly Volatile Climate. Pakistan ranks fifth globally on the Climate Risk Index, and is expected to see increasing occurrence and severity of extreme weather events. The country is affected by multiple climate risks; a warming rate considerably higher than the global average, water scarcity and intensifying droughts alongside flooding since 2010, and worsening air quality.

An adolescent in Pakistan today – i.e. a young person between the ages 10 and 19 years – will experience more floods, crop failures, droughts, heat waves and air pollution over their life time than an adolescent in the 1970s. Extreme climate events bring with them staggering human and economic costs[i], exacerbating existing vulnerabilities and widening inequalities.

Young people are going to be the primary bearers of the high human and economic costs of climate change, which threaten their health, education, well-being and futures. Younger men and women and the differently abled from marginalised backgrounds are disproportionally disadvantaged due to their precarious and limited access to basic services, social protection schemes and other coping mechanisms. Their heightened exposure to multiple extreme climate events raises vulnerabilities manifold and leads to the transmission of negative shocks across generations, such as reduced incomes and opportunities for young people.

Extreme Climate Events Disrupt Education Trajectories

Extreme climate events damage service delivery infrastructure and compromise the ability of students to access, engage and learn in schools. Almost all children around the world are now exposed to at least one major climate shock in their lifetime. This exposure is far worse for adolescents and children in the global South, where recent improvements in access and learning have been reversed due to worsening severity and frequency of extreme climate events.

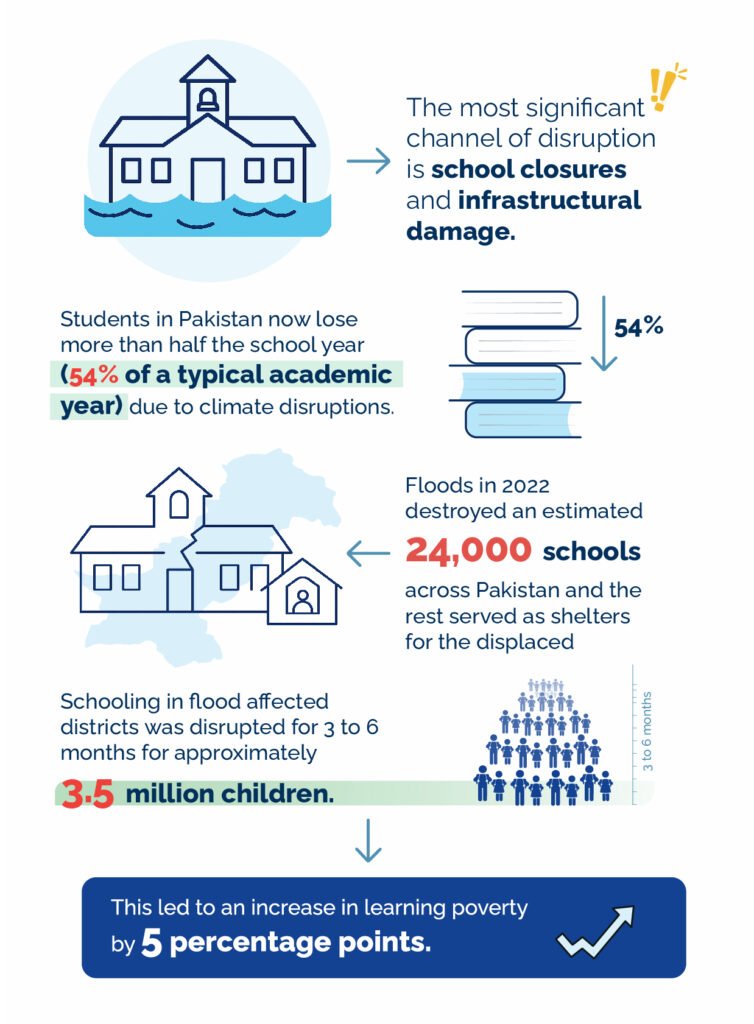

Figure 1. Consequences of Climate Disruptions for Educational Outcomes

Air pollution and heat waves are now routinely associated with school closures and prolonged school holidays. Schools in Lahore remain closed for between 2 to 4 weeks on average every year during smog season. Evidence from countries in the global South shows that high heat reduces in-class engagement, concentration/ability to focus and is associated with lower learning outcomes.

This disrupted access is temporary for some but permanent for others. Girls in particular are especially vulnerable. A large number of girls in Sindh dropped out of school because of flood-related closures and never went back. Countries across South Asia, including Pakistan have registered a rise in early marriages for girls as a direct response to economic shocks or insecurities and displacement linked to climate. The health and economic shockwaves triggered by extreme climate events push millions of people into poverty, resulting in both girls and boys dropping out of schools

Seeking Solutions within Lived Experiences

There is little documentation of the ways in which climate shocks compound threats posed by poverty and underdevelopment to the education and life trajectories of millions of young people in Pakistan. Exposure to and experience of climate change is likely to vary by geography, gender and socio-economic class. While proposed adaptation strategies suggest a role for students as change-agents, this role remains undefined in the context of countries and communities in the global South. Imagined and designed solutions for mitigation and adaptation must account for the voices and experiences of these young people.

Some evidence of climate distress is beginning to emerge from studies in the global South. However, for Pakistan there is at best anecdotal evidence on the experiences of communities living through the rapid climate changes. The public, academic and policy discourses feature policy makers, teachers, journalists and climate activists; yet none speak directly to the young people.

As we move to develop strategies to increase climate resilience, it is imperative that we look to the communities and the students themselves. The climate and education policy actors, and service design and delivery structures must imagine active and substantive roles for adolescents in climate risk mitigation and adaptation strategies, rather than considering them passive victims of climate shocks. This requires ensuring adolescents are supported through required knowledge and skill-building for living in and coping with a volatile climate. For example, Pakistan can embed disaster education into the existing curriculum in much the same way as that done in other countries as Cambodia and Thailand have done. Such changes to the curriculum and other steps need to be informed by young people’s lived experiences of the types of threats they face, be it drought-related water stress, food insecurities or extreme heat.

Figure 2. DARE-RC Study on Schooling Strategies and Climate Change

[1] The cost of illness and premature death from air pollution was estimated at equivalent to 2% of GDP annually in 2016. A third of the country underwater with 33 million people displaced. The total damage due to these floods was estimated to be equivalent to 4.8% of the years’ GDP, while recovery and reconstruction needs were projected to be 1.6 times the budgeted national development expenditure for 2023. The floods also caused a decline of in GDP estimated at nearly 2.2% of FY22 GDP.

Authors: Dr Hadia Majid (Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Economics, LUMS), Dr Rabea Malik (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives), and Ms Fatimeh Munawar (Research Assistant, DARE-RC)

Copy-Editor: Maryam Beg Mirza (Assistant Consultant, Education at OPM)

Quality Assurance: Dr Sahar Shah (Senior Research Manager, DARE-RC)

Design: Sparkom Media

The views expressed in this blog are that of the author and do not reflect the views of DARE-RC, the FCDO, and implementing partners.

One Response

Very insightful